A step closer to stronger federal IoT security

On Tuesday September 15th, the US House unanimously passed the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act [H.R. 1668]. The bill, sponsored by Reps. Kelly and Hurd, would require federal procurement and use of IoT devices to conform to basic security requirements. The version passed by the House makes several improvements compared to previous versions and the Senate companion, which we blogged about in detail a long time ago in the parallel dimension that was 2019. Although the chances of Senate passage are unclear, the bill’s resounding approval in the House is a big step closer to a meaningful IoT security framework across federal agencies.

Bill summary

The House-passed version of the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act retains its basic formula:

- NIST must issue standards-based guidelines for minimum security of IoT devices owned or controlled by the federal government. [Sec. 4(a).]

- The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) must issue rules requiring federal civilian agencies to have information security policies that are consistent with NIST’s guidelines. [Sec. 4(b).]

- Federal acquisition rules must be updated to reflect the IoT security standards and guidelines. [Sec. 4(d).]

- Federal agencies must implement a vulnerability disclosure policy, as well as contractors providing information systems to agencies. [Sec. 5-6.]

- Federal agencies cannot procure, obtain, or renew contracts for IoT devices that cannot meet the security guidelines. [Sec. 7.]

Broadly speaking, this is pretty thoughtful and should have a meaningful impact on federal IoT security. Let’s zoom in on a few details: 1) The definition of IoT; 2) The waiver process; and 3) The contract amount threshold.

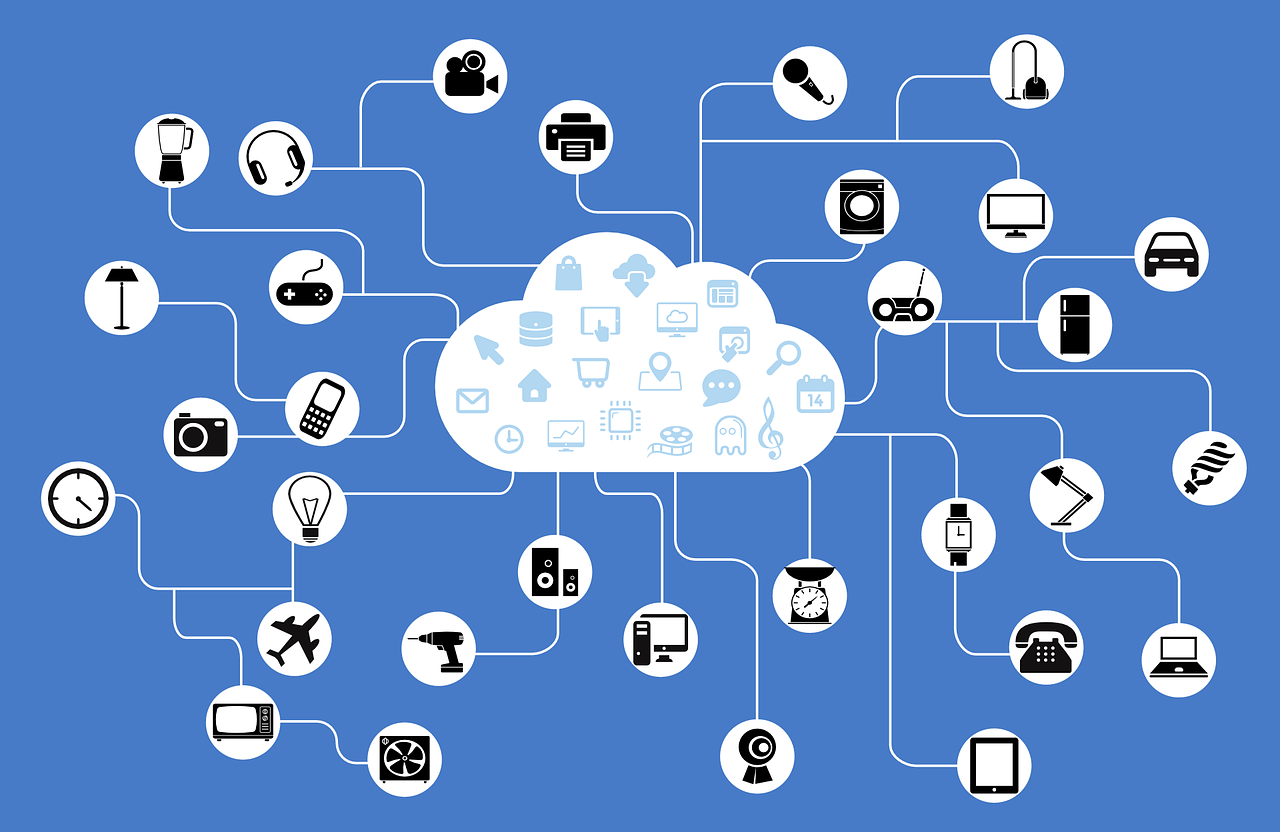

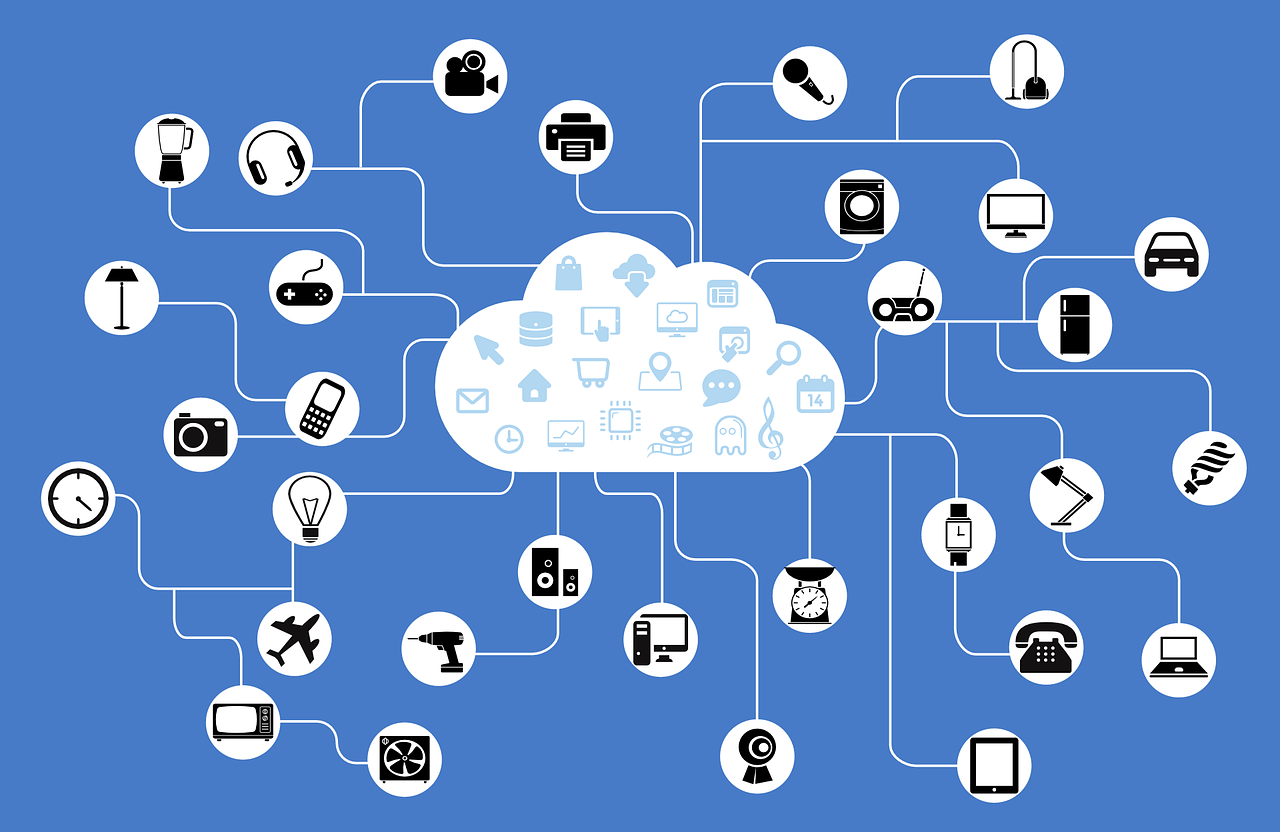

IoT Definition

We note the bill’s definition of IoT leverages NIST’s definition of IoT from NISTIR 8259. Here is that definition:

Devices that have at least one transducer (sensor or actuator) for interacting directly with the physical world, have at least one network interface, and are not conventional Information Technology devices, such as smartphones and laptops, for which the identification and implementation of cybersecurity features is already well understood; and (B) can function on their own and are not only able to function when acting as a component of another device, such as a processor. [Sec. 4(a)(1).]

This workable definition of IoT avoids some of the problems we flagged with the original bill, in which items like Programmable Logic Controllers were categorized as general computing devices. This is positive, as is the definition’s alignment with NISTIR 8259. Consistency is always A+. Although the definition would not cover disassembled components of an IoT device – such as commodity processors, actuators, sensors, etc. – this is understandable since it is literally a definition of “IoT device.” And while the components alone may not be covered by the proposed security rules for Iot devices, such as those established under Sec. 4(a)-4(b), they would be covered once they are assembled into a device and controlled or used by the agency.

Waiver process

In another positive development, this House-passed version of the bill improves upon the problematic waiver process we flagged in our previous blog post. The most recent Senate bill provides a waiver from the security requirements when the use of the IoT device is “appropriate to the function of the [device],” which blows a giant loophole into the bill by exempting (for example) smart light bulbs that are used as smart light bulbs. The House-passed version changes this up by allowing the waiver if the IoT “device is secured using alternative and effective methods appropriate to the function of [the] device.” [Sec. 7(b)(1)(C)] This approach is far more appropriate for the goals of the bill, and we hope the Senate makes a similar modification at the next available opportunity.

Contract amount threshold

Alas, not all is wine and roses. The bill includes a confusing provision that seems to limit the security requirements for IoT procurement to small-ish contracts. Specifically, Section 7(a)(2) states that the prohibition on procurement and use of IoT devices that do not meet the NIST security guidelines applies to contracts that are not greater than the “simplified acquisition threshold” – which is $750,000.

At first glance, and also second glance, this looks like the procurement security requirements do not apply to IoT contracts over $750,000, which would be consequential considering the large size of many government purchases. However, staff close to the bill inform us that their intent is the opposite: The procurement security requirements do apply to contracts both above and below $750,000, and the “simplified acquisition threshold” needed to be called out separately to ensure that coverage. Fair enough, but the provision would benefit from a clarification on this point.

More federal leadership to come?

Let’s take a look at the bigger picture. By now, numerous assessments from Very Smart People conclude that the exploitability of IoT devices is a pressing global cybersecurity problem. To focus on the federal government’s own findings, behold the Cyberspace Solarium Commission report, the report on automated threats from the Departments of Commerce and DHS, and the Commission to Enhance the National Cybersecurity report of yesteryear. Rapid7’s analysis of the security landscape concurs with such assessments, and – combined with our concern that basic IoT security best practices are well-known but still not broadly adopted – has led to our stated position that some regulation encouraging the adoption of baseline security measures is appropriate.

Some federal agencies (notably the FDA) have taken action to demand basic security of the devices in their jurisdiction, and NIST is doing pretty fine work in establishing a voluntary minimum IoT security baseline. However, in general, the more cross-cutting and bold regulatory action on IoT security is being led by individual states (specifically California and Oregon) and non-US countries (such as the UK), which are requiring devices to include a small subset of basic security protections. But at the federal level, Congress is at risk of being late to the game on the issue of IoT security, despite studying it a great deal.

Passage of the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act in the House takes us a step closer to changing that, and enactment into law would go a long way to putting the US into a leadership position on this issue. Though the bill is narrowly focused on government use and procurement, it makes sense for the federal government to take the lead in raising the bar for devices it buys and manages. Leading by example may also jumpstart Congress’ process of exploring an appropriate IoT security regulatory framework for the private sector – one that is effectively consistent with industry best practices and heads off a patchwork of state laws.

One step at a time

Representatives Kelly and Hurd deserve hearty elbow-bumps for getting this over the finish line in the House. Senators Gardner and Warner, to their great credit, are also pushing to fast-track this bill in the Senate. Unfortunately, the legislative calendar is not too favorable as the election-pandemic-wildfire-recession year draws to a close, and failure to pass the bill would mean both the House and Senate must start over in 2021.

Nonetheless, the progress in the House this week boosts the chances for advancement in the Senate (in 2020 in 2021), which would be good news for federal agency security, cybersecurity writ large, and federal leadership on IoT security.

If you like the site, please consider joining the telegram channel or supporting us on Patreon using the button below.