Could Apple’s new MacBooks signal a change in direction on security?

Apple recently announced a new line of completely overhauled MacBook Pros. Much has been written about their new design, new chips, new displays, new keyboards etc, but I thought I detected something else that might be new about these MacBooks too: A new approach.

The updated laptops may be the first sign of a shift in product management strategies at Apple. Product management—the process of directing the development and evolution of some product—is hard, and Apple has made some missteps in recent years. From the outside looking in, those missteps have resulted in challenges both within their products, but also relating to the security of their products.

It starts with solving problems

One of the most important principles of product management is to focus on problems to be solved. You have to start with a problem that your customer (or potential customer) has, and work from there to find a solution that makes sense for your product and your customer base. If your product does not solve a problem for anyone—even if that problem is a rather first-world problem like, “It’s a rainy weekend and I’m bored”—then nobody’s going to use it.

It’s a big product management no-no to just try to build something you think is cool and ship it, and let marketing figure out how to make it sell. That can certainly be a recipe for success, if you’re lucky and you’re fairly in touch with the market. But it can also be a big recipe for failure.

Consider the case of Juicero, an Internet of Things (IoT) device that could be controlled wirelessly and allowed you to… make juice. The product was intended to be similar to a Keurig, but for people who wanted juice instead of coffee. However, juice drinkers don’t have the same needs as coffee drinkers. The device and the juice pouches were expensive, and there were cheaper and easier ways to get your juice. Worse, it was discovered that you could use a pair of scissors to cut open the pouch, squeeze it into a glass, and get the same glass of juice that the machine would have produced.

Juicero was a failure, because it didn’t solve a problem for many people, and even among those who might have considered such a device, it didn’t solve the problem better than a cheap pair of scissors.

Working backwards from the problem to the features or products is something that Apple has experience with. Consider the response Steve Jobs gave back in 1997 when he got a question about why Apple was dropping support for OpenDoc.

So, Apple’s good at solving customer problems?

Well, yes and no. They’ve definitely had some success there in the past, but in recent years, it often feels like the things Apple produces are the result of someone in a back room somewhere saying, “Hey, I’ve got this cool idea,” and then building it without customer input. Let’s take a look at some examples.

In 2016 the Touch Bar was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.

The Touch Bar was, apparently, Apple’s compromise for a touch screen. Apple has always been against touch screens on the Mac, for reasons that I believe are quite valid. However, Apple had been getting heat from reviewers for years, who touted the touch screens on latest Windows PCs as a reason to buy them instead of a Mac.

Thus, the Touch Bar was born. Unfortunately, it solved a problem for Apple, but it didn’t solve a problem for most users. Although some learned to like it, hate for the Touch Bar is widespread.

Apple also released MacBook Pros that eliminated all ports other than USB-C, and with the infamous butterfly keyboard that was as fragile as its namesake. This was done for the sake of making laptops that were thinner and lighter. However, it turned out most people cared less about thinner and lighter and more about the things that had been taken away. The Internet has been awash in keyboard and dongle jokes, poking not-so-good-natured fun at Apple and the MacBook Pros, ever since. This created more customer problems than it solved.

And all this relates to security how?

Some of Apple’s recent security changes have addressed security issues, but they don’t seem to have taken their users’ problems and perspectives into consideration.

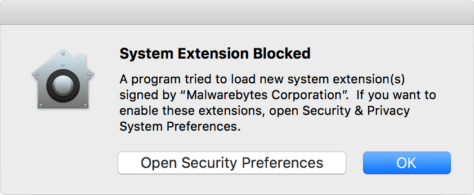

As an example, Apple decided to start restricting installation of kernel extensions in macOS 10.13 (High Sierra). The intent was to prevent malicious software from installing a kernel extension (kext) surreptitiously. This was done by asking the user to approve installation, via the following message:

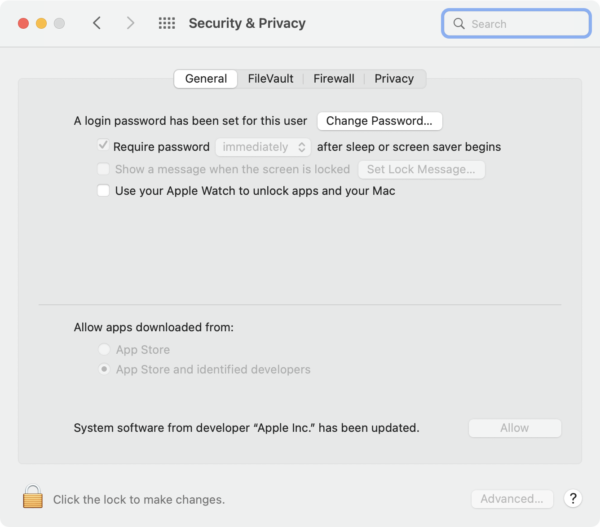

In order to actually enable the kernel extension, users would have to click the button to go to Security Preferences, and then would have to figure out what they were supposed to do there, which was not so obvious. There was an Allow button in System Preferences that would need to be clicked, but Apple’s messaging never indicated that’s what you should do. Worse, the Allow button would only stick around for a few minutes before disappearing… so if the user didn’t click it right away, they’d be stuck.

Most of the cases where users saw these warnings were for legitimate software, not for malware. This solved a problem that Apple wanted solved, but from the user’s perspective, it caused more problems than it solved. Third-party software has had to take a lot of responsibility for filling in the gaps in the user experience as best it could. I know from first-hand experience!

I understand why Apple did it this way, but even so, the user experience needed a lot of work—and still needs work, as Apple has carried this experience over to the new system extensions that have replaced kernel extensions.

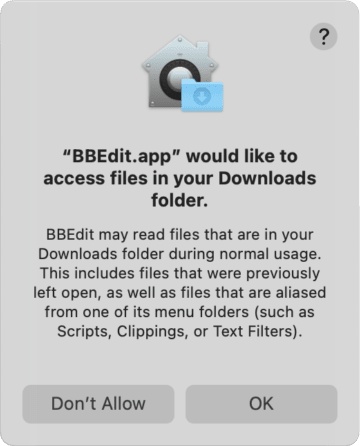

Next, Apple decided to protect certain locations on disk, to protect users’ security as well as their privacy. This is a noble goal, but it resulted in a cascade of new alerts that hassled users, who became frustrated and got in the habit of just clicking OK to make these alerts go away.

It’s important to note that Apple’s use of an OK button in this alert is problematic, as users have gotten used to simply clicking OK or Cancel to make these things go away. Yet clicking OK, in this case, has a definitive action of allowing an app to access your data! Worse, if you re-think that action afterwards, figuring out how to reverse your decision (assuming you even realize that you made a decision) is quite difficult for the average user. Not good.

Again, this solved a problem that Apple perceived, but not one that most users knew even existed. Amusingly, Apple did this in a way that they’d made fun of Microsoft for doing years before.

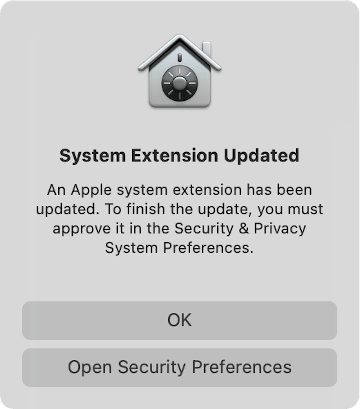

Another example relates to something I’ve just seen very recently. Out of the blue, not following any particular system update or software installation that I was aware of, I got a message on my Mac asking me to approve a mysterious, unnamed system extension.

The alert says it’s an Apple system extension, so I guess it must be okay, right? Not really. If I were crafting a message like this to be displayed by a piece of malware or a scam website, I’d make sure it claimed to be associated with Apple.

Visiting System Preferences didn’t clear anything up, unfortunately.

From a little detective work, assisted by Howard Oakley’s SystHist app, I was able to determine that this was most likely the result of an update silently and automatically installed on October 7, which updated a system kernel extension named AppleMobileDevice.kext. This is a legitimate Apple extension, located in the read-only /System/Library/Extensions/ folder.

Now, after all my complaining earlier about how Apple has made third-party developers go through this process, you might think I’d be happy to see that they apparently haven’t exempted themselves. However, you would be wrong.

In this case, Apple has implemented something in as close to the worst possible way that I can think of. This message instills fear and uncertainty. Something has been updated, but it’s apparently not working right! In order to solve this problem, I’m expected to trust what the alert tells me and go click a button.

Isn’t this more or less exactly what security professionals have been telling people not to do for years? If you see a weird link or button somewhere and you weren’t expecting it, don’t click it. Yet this is exactly what Apple is expecting people to do.

This behavior encourages insecure behavior, and will cause more security problems for people than would be caused by macOS simply automatically trusting one of Apple’s own kernel extensions. Once again, this solves an Apple problem at the expense of the customer, who now has a problem they didn’t have before.

So, is it time to move away from the Mac?

Whoa, there, let’s not do anything crazy like switching to Windows!  Microsoft isn’t any better, and the good news is that there’s some hope that things are changing for the better. In October, Apple announced the release of a new MacBook Pro line. Okay, yes, I hear you… doesn’t Apple announce new Macs about once per year? What’s so special about this?

Microsoft isn’t any better, and the good news is that there’s some hope that things are changing for the better. In October, Apple announced the release of a new MacBook Pro line. Okay, yes, I hear you… doesn’t Apple announce new Macs about once per year? What’s so special about this?

What’s most interesting about the new MacBook Pros are not the M1 Pro and M1 Max chips… it’s that this new line brings back a real keyboard, with real function keys instead of a Touch Bar, and brings back all the ports people were upset about losing. This may not seem like much, but it’s actually quite rare for Apple to walk back changes it’s made, especially to this degree.

Does this mean that Apple is once again starting to pay closer attention to the problems their users are experiencing? Perhaps. It’s definitely a good sign. They’ve looked at user problems that have emerged as a result of their actions, and they have made changes to address those problems, rather than just continuing to barrel forward to the next “cool” feature.

If we’re lucky—and noisy!—perhaps this problem-focused trend will trickle down to security development, and the user experience for some of the recent macOS security features will improve.

Maybe I’m reading more into one product release than I should be. Still, I choose to hope for a better tomorrow.

The post Could Apple’s new MacBooks signal a change in direction on security? appeared first on Malwarebytes Labs.

If you like the site, please consider joining the telegram channel or supporting us on Patreon using the button below.

![Cobalt Strike Beacon Detected - 47[.]111[.]117[.]176:443 7 Cobalt-Strike](https://www.redpacketsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Cobalt-Strike-300x201.jpg)