Dox, steal, reveal. Where does your personal data end up?

The technological shift that we have been experiencing for the last few decades is astounding, not least because of its social implications. Every year the online and offline spheres have become more and more connected and are now completely intertwined, leading to online actions having real consequences in the physical realm — both good and bad.

One of the most affected areas in this regard is communication and sharing of information, especially personal. Posting something on the internet is not like speaking to a select club of like-minded tech enthusiasts anymore — it is more akin to shouting on a crowded square. This gives rise to many unique threats, from cyberbullying and simple financial scams to spear phishing and social engineering attacks on business executives and government officials. And while awareness of privacy issues is increasing, much of the general public still only have a basic understanding of why privacy matters.

Unfortunately, even if we take good care of how and with whom we share our personal data, we are not immune from being doxed. The abusers may be motivated enough to go beyond gathering data available in the public domain and turn to the black market in the hope of finding personal information that will do real harm, for instance, gaining access to social media accounts. In this report, we will dig deeper into two major consequences of (willing and unwilling) sharing personal data in public — doxing (the public de-anonymization of a person online) and the selling of personal data on the dark web — and try to untangle the connection between the two. We’ll’ also look at how these phenomena affect our lives and what challenges these conditions present to users.

Key findings

- Doxing is not something that only vulnerable groups or people with specific professions, such as journalists or sex workers, can be affected by. Anyone who voices an opinion online may potentially become a victim of doxing.

- Almost any public data can be abused for the purpose of doxing or cyberbullying with an unlimited number of ways users can be harmed by their own data.

- With increasing digitization of most aspects of our everyday lives, even more data is now shared with organizations and may end up in the hands of criminals. This now includes personal medical records and selfies with personal identification documents.

- Access to personal data can start from as low as US$0.50 for an ID, depending on the depth and breadth of the data offered.

- Some personal information is as mch in demand as it was almost a decade ago – primarily credit card data and access to banking and e-payment services. The cost of this type of data has not fallen over time and that is unlikely to change.

- Data sold on dark market websites can be used for extortion, executing scams and phishing schemes and direct stealing of money. Certain types of data, such as access to personal accounts or password databases, can be abused not just for financial gain but also for reputational harm and other types of social damage including doxing.

Unwanted spotlight: doxing

The increasing political and social division of recent years combined with a perceived anonymity exacerbates some of the corresponding social dangers on the internet, such as trolling and cyberbullying. And at the intersection with privacy threats there is the issue of doxing.

What is doxing?

Historically, doxing (also spelled doxxing) meant de-anonymizing a person on the internet, especially in early hacker culture, where people preferred to be known by their nickname (online handle). The meaning has evolved, however, to have a broader sense.

Doxing is, in a way, a method of cyberbullying. It occurs when a person shares some private information about another person without their consent to embarrass, hurt or otherwise put the target in danger. This can include sharing:

- embarrassing photos or videos;

- parts of private correspondence, probably taken out of context;

- a person’s physical address, phone number, private email address and other private contacts;

- occupation and job details;

- medical or financial data, criminal records.

EXAMPLE: An example of a threat of doxing in this classic sense is the story of the anonymous blogger Slate Star Codex, who claimed that a New York Times journalist insisted on publishing his real name in a piece about him. This prompted the blogger to delete his blog. Luckily, the newspaper seems to have abandoned the idea.

Doxing also includes cases when data about the victim is already publicly available, but a perpetrator gathers and compiles it into an actionable “report”, especially if also inciting other people to act on it. For example, if a person voices an opinion on a divisive issue in a post on a social network, throwing in their phone number in the comments and suggesting people should call them at night with threats is still doxing, even if the phone number is available online in some database or on some other social network.

EXAMPLE: A journalist from Pitchfork, a US music outlet, received numerous threats on Twitter including suggestions to “burn her house” after her phone number and home address were published by Taylor Swift fans who were unhappy about a review of the singer’s latest album that wasn’t positive enough.

Why is doxing dangerous?

Compared to the physical world, information on the internet can spread very quickly and is almost impossible to remove once posted online. This makes doxing even more harmful.

The most common goal of doxing is to cause a feeling of stress, fear, embarrassment and helplessness. If you are caught in a heated argument on Twitter, and somebody posts your home address and suggests that people should hurt you, it naturally causes anxiety. Threats can also be directed at your relatives. The real danger, however, comes if someone decides to actually carry out the threats, which means doxing also threatens your physical safety — something that happens more often than you would think.

Besides posting your information online for everyone to see, attackers can share it in a targeted way with your relatives, friends or employer, especially if it is embarrassing. This can harm the victim’s relationships with their loved ones, as well as their career prospects.

EXAMPLE: After a service for finding people using only a photo gained popularity in VK, a popular social network in Russia, it was used to de-anonymize women who starred in porn movies or worked in the sex industry. The perpetrators specifically suggested sharing this information with their relatives. One of the victims was a school teacher who eventually lost her job.

Doxing scenarios

How can you be doxed? These are some common scenarios and how they can harm the victim:

- Identifying the user and sharing information directly with their employer, which results in the person getting fired due to social pressure;

- Leaking intimate photo and video content of a user to the public — an activity that is often called ‘revenge porn’ is a widespread method of attacking one’s privacy with malicious intent that can have significant consequences for the victim;

- Revealing the identity of anonymous bloggers, internet users, opinion leaders and creators, which can lead to real danger if the victim is in a hostile environment, for instance, opposition bloggers in certain countries or a person who supports unconventional views;

- Outing the person and providing their personal details in the media when this information does not serve the public interest and may directly harm the person;

- Gathering and sharing information about the account of a specific person (the potential victim) featured in sensitive or questionable content with hostile groups or accounts that may engage in online or even offline violence against that person.

Social impact

Doxing is a very pressing matter in times of increasing social and political division. Doxing, as well as the threat of doxing, hampers freedom of speech and produces a chilling effect. It prevents people from voicing their opinions, which is harmful to democracy and healthy social debate.

Some people are more likely to be victims of doxing. Journalists, bloggers, activists, lawyers, sex industry workers, law enforcement officers all run a higher risk of being doxed. For women, doxing goes hand in hand with sexualized verbal abuse and threats. For law enforcement officers, it also means direct danger for their physical safety, especially for undercover officers. This can lead people to abandon their jobs.

High-profile internet personas are more at risk than average users. It doesn’t mean that “ordinary” people are safe from doxing. Having said something online or done something on camera that “upsets” a large group of people can randomly attract excessive attention from online crowds and turn your life into a nightmare — even if you never actually said or did it in the first place.

EXAMPLE: Tuhina Singh, a CEO of a Singapore company was doxed: her phone number and private email address were published online, resulting in insults and threats. Reason? She was misidentified as a woman from a viral video, refusing to put on a mask amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The darknet database. How much do you cost?

Doxing is the result of abusing information that is available in the public domain and not used for financial gain. However, the threats to personal data and, hence, personal safety, do not end there. Aside from the publicly available data that we freely share and that can be gathered by anyone and used for malicious purposes, the organizations we share our data with don’t always handle it responsibly.

By definition, we do not expect this information to leak out into the public and even if it does, do not anticipate that it might harm us. According to recent research by Kaspersky, 37% of millennials think they are too boring to be the victim of cybercrime. The number of massive data leaks hit a new high this year and we no longer get surprised by yet another company being hacked and their customers’ data being leaked or used in ransom demands.

Efforts to better protect personal data are being made in a variety of countries, with governments imposing new directives to ensure protection and penalize irresponsible management of citizens’ data. New personal information protection directives such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU and Brazilian General Data Protection Act (LGPD), as well as increasing customer scrutiny towards data handling practices, have forced organizations to improve their security and take the data leakage threat more seriously.

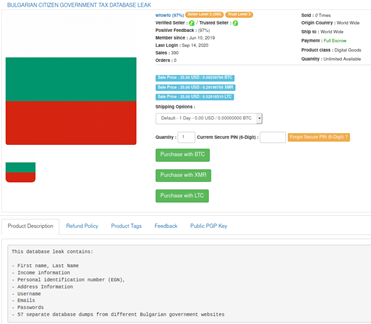

However, that doesn’t mean the data is safe. In some cases, stolen data is used for ransom practices, in others it is published out in the open. Sometimes it is a mix of both: threat actors who employed the Maze ransomware published stolen data if they did not succeed in getting the ransom money. But most of it ends up on the dark web as a commodity, and a very accessible one. Darknet forums and markets, essentially marketplaces for illegal physical and digital goods, are used by cybercriminals to sell services and products, from malware to personal data.

Our experts, who specialize in understanding what goes on in the dark web, researched the current state of data as a commodity on such platforms to find out what kind of personal data is in demand, what it is used for and how much it costs.

Methodology

For the purposes of this research we analyzed active offers on 10 international darknet forums and marketplaces that operate in English or Russian. The sample included posts that were shared during the third quarter of 2020 and that are still relevant.

Research findings – how much do you cost?

Covering all types of personal data offers on the dark web would turn this report into a short book, so it focuses on just some of the most popular categories available on dark markets. However, it is important to mention that the types of databases leaked and then sold on the dark web vary, which is unsurprising considering they are stolen from different institutions and organizations. Leaked databases can be cross-referenced and this way made even more valuable, as they present a fuller picture of a subject’s personal details. With that in mind, let’s dig into what is out there in the shadows that cybercrooks might have on you:

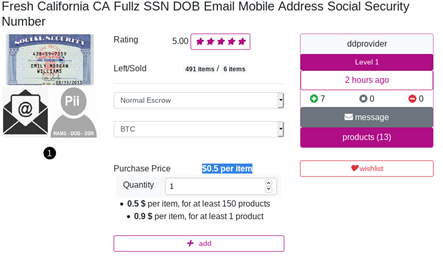

ID card data: $0.5 – $10

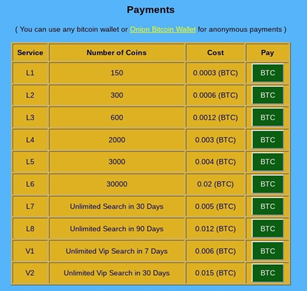

Identity documents or ID cards are the main means of identification in most countries, including the US and throughout Europe. Usually they are tied to the most important services, especially state services and contain sensitive information such as social security number (SSN) in the US. Though important, the cost of these documents on the black market is not that high and depends on how full the information is. For instance, information with a full name and insurance number will cost as little as $0.50 per person, while the price for a ‘full pack’ including ID number, full name, SSN, date of birth (DOB), email and mobile phone can reach up to $10 per person. The price also varies depending on the size of the purchase – data sold in bulk is cheaper per unit.

Purchasing 150 ID cards will cost as little as 50 cents per unit

Data from identity documents can be used for a variety of scams, filling out applications for specific services and gaining access to other sensitive information that can later be used for criminal purposes.

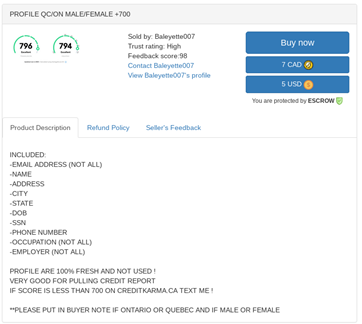

Sometimes the leaked databases contain much more than just ID info

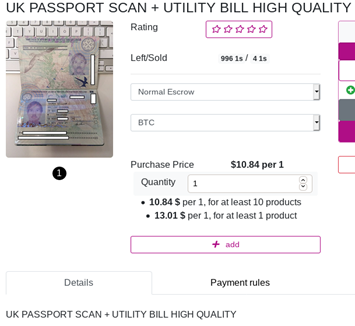

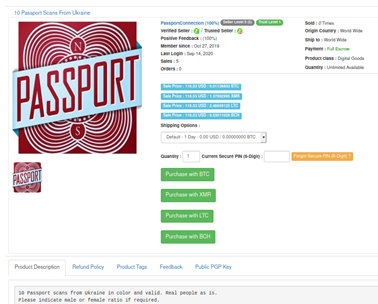

Passport scans: $6 – $15

Passports are another type of identification document that are popular with cybercriminals. In some countries such as Russia, Ukraine and other former Soviet states they are used instead of IDs and are required to receive pretty much any government-related or financial service – from filing a complaint in a shop to taking out a loan. In other countries, passports can also be used for identification on international platforms such as cryptocurrency exchanges – or for international fraud.

This is the reason passport scans go around the web quite often – think of how many times you have uploaded a copy of your passport to some service, sent it to an organization or allowed them to scan it themselves.

Passport scans are more expensive than identification details with prices varying from $6 to $15 depending on the quality of the scan and the country of origin. Typically, there are two types of passport scans sold – a scan of the first page which, understandably, is cheaper than a scan of a full passport.

Passport copies for purchase can be selected by gender if required

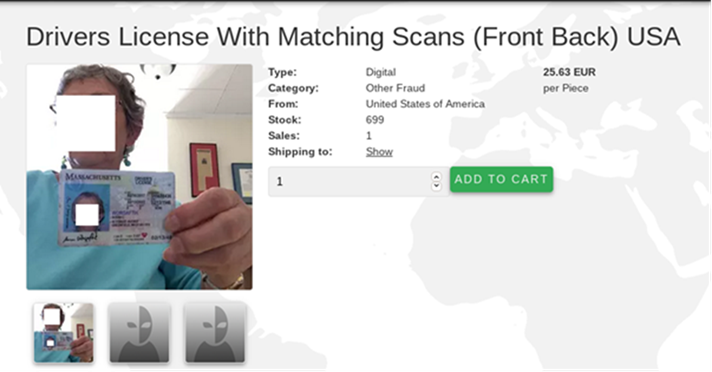

Driver’s license scans: $5 – $25

Driver’s licenses are another type of identification document that is in demand in the shadows, primarily due to the growing number of services that one can register for using a driver’s ID. Typically, the information sold on forums includes a scan of the license with full information. Varying in price from $5 to $25, these can be used by cybercriminals for car rental, as an ID for local services or insurance fraud.

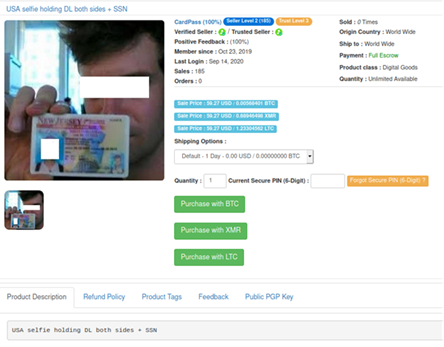

Selfie with documents: $40 – $60

Have you ever taken a selfie with your passport or ID? User identification is taken more seriously these days with organizations adhering to so-called know-your-customer (KYC) programs that require identity verification for various operations. For instance, cryptocurrency exchanges employ this practice to prevent money laundering by getting people extracting funds to confirm they are who they say they are. Social networks require selfies with documents when users need to recover access to their account and bank employees take pictures like these when delivering credit cards to clients’ homes.

Using stolen passport or ID selfies allows fraudsters to bypass KYC guidelines and continue to launder money. These documents can also be used for a whole variety of services – from car rentals to getting micro-loans or manipulating insurance companies. Such documents allow cybercriminals to enter the cache or execute their schemes, and even blackmail the people identified in these documents. As a result, this data is very valuable, varying from $40 to $60 per person.

Selfies with identification documents can be used to bypass a service’s security procedures

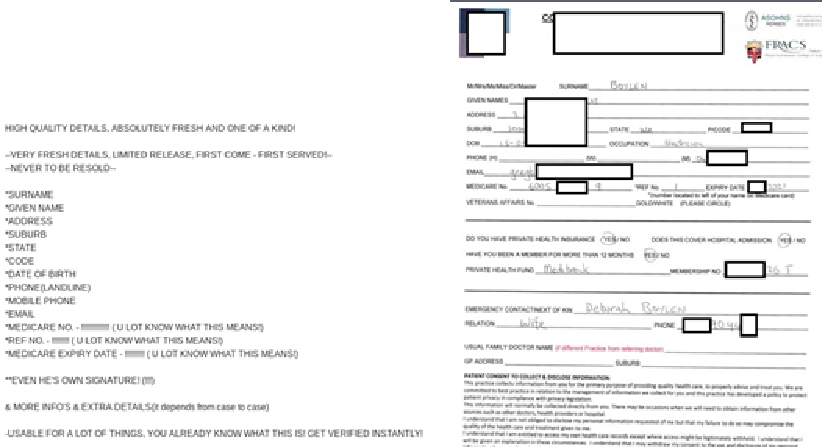

Medical records – $1 – $30

The world is becoming more digitized along with certain aspects of our lives that we never thought would go online. Take medical records, for instance – cybercriminals have laid their hands on them too. Looking back to 2012, when we analyzed different types of data available in the darknet, medical data was not even a thing. Now, however, this data is in demand as it can be used for a whole variety of fraudulent activities from obtaining health insurance services to purchasing regulated drugs. It can also be used to demand ransom. Recently, for instance, Vastaamo, a Finnish mental health organization, was hacked and the data of their patients, including children, stolen and later exposed on dark web markets, with at least two thousand patients affected. The hackers initially demanded a ransom payment to delete the information, but then switched their attention directly to the patients.

Leaks of medical information can become very unpleasant as they put the victims who are already vulnerable into an even more vulnerable position. The type of data shared on the darknet varies from a medical form with a full name, email, insurance number, and the name of the medical organization to a full medical record of a patient – with their medical history, prescriptions and more.

Medical records sold on darknet forums can vary from full information about a person to forms from medical institutions

Credit card details: $6 – $20

Credit card details fall under the category of most basic information stolen and used by cybercriminals. Full credit card information including the name, number and CVV code can be used to withdraw funds or purchase goods online and is valued from $6 to $20 per unit. Back in 2012, our evaluation put the price at $10. On average, the cost is more or less the same. The price for such data is dictated by the country of origin, the bank and more importantly, on how large the purchase is, with ‘better’ value with larger volume purchases. Of course, new anti-fraud banking systems are making life harder for cybercriminals, forcing them to constantly come up with new ways to cash out. Nevertheless, with credit card details being the starting point for most of these schemes, they are nowhere near becoming outdated.

Online banking and PayPal accounts: $50 – $500

Another type of financial data is online banking access and PayPal account information. Both provide direct access to the funds of the victims with PayPal being a sweet spot for the cybercriminals who want to launder their money and withdraw it without any security checks. Access to online banking is generally valued at between one and 10 percent of the funds available in the account, while PayPal accounts cost from $50 to $500 depending on the available credit and previous user operations.

Subscription services: $0.50 – $8

In the world of subscription-based entertainment, access to popular streaming, gaming or content platforms is in high demand. While little personal information is given away, losing access to one’s account on Netflix, Twitch or PornHub is not something that anyone would enjoy. Stolen subscription service credentials are not only sold on only in the dark web – they can be found in some shady regular forums too. The dark web usually has offers to purchase access details in bulk, which can later be sold individually to multiple customers. The price for access to such services varies from 50 cents to $8.

| How much does your data cost? | |

| Credit card details: | $6 – $20 |

| Driver’s license scans: | $5 – $25 |

| Passport scans: | $6 – $15 |

| Subscription services: | $0.50 – $8 |

| ID (full name, SSN, DOB, email, mobile): | $0.50 – $10 |

| Selfie with documents (passport, driver’s license): | $40 – $60 |

| Medical records: | $1 – $30 |

| Online banking account: | 1-10% of value |

| PayPal accounts: | $50 – $500 |

Password databases

Leaks of password databases are among the most widespread data leaks. From retail loyalty cards to logins for banks, such databases have been appearing on the dark web and even on the normal web for years, and they have a tendency to be leaked into the public domain, requiring very small payments to access them, or sometimes access to the data is entirely free. While these databases are outdated for the most part, they still represent a real danger. Users tend to use the same passwords across a number of platforms and accounts, often tying them all to the same email. Picking up the right password for a specific account is often a matter of time and effort, and as a result, users are at risk of having more of their data compromised – from their social network accounts to their personal email or private accounts on adult websites. Access to other accounts can later be resold (as in the case of subscription services) or used for blackmail or scam.

Certain services aggregate leaked passwords and enable paid subscription-based or single time access to their databases as shown on the screenshot. The service on the screenshot allows one database check for 30 coins

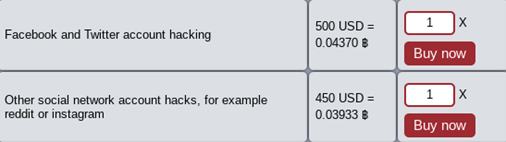

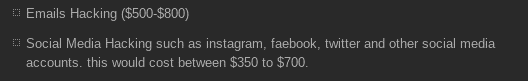

Unauthorized access to email and social media: $400 – $800

With so much personal data available for sale, one may wonder whether purchasing access to someone’s email or social network account is also as easy as obtaining IDs. The darknet operators do indeed offer to hack into specific accounts or emails, charging from $400 per account. However, the methods employed by those who offer such services are rather basic – they can only go as far as trying to guess the password or checking the account against existing leaked databases or executing social engineering attacks to get the user to reveal their password. Increased security of social media and email services has also made these practices less successful with double authentication and various other security measures protecting users better than before. As a result, most of these kinds of offers on dark markets are, ironically enough, actually scams against other cybercriminals.

Examples of forum advertisements offering to hack social media accounts and emails

Nevertheless, this doesn’t rule out the possibility of real targeted account hacking – more covert, technically complex methods are employed by experienced actors and these services usually cost a lot. For instance, the actor may identify a specific email of the potential victim, send a spear-phishing email prompting the target to download malware that will be able to collect information about the passwords and ultimately gain access to the targeted accounts. These services, however, are extremely expensive, time consuming and are usually executed by advanced threat actors against priority targets.

Key takeaways

In the course of this research we have witnessed a number of trends relating to stolen and repurposed personal data. Some personal information remains as much in demand as it was almost a decade ago – primarily credit card data and access to banking and e-payment services. The cost of this type of data has not fallen over time and that is unlikely to change.

Another big change is the type of data now available for sale. With the digitization of medical institutions, personal medical records traditionally categorized as very sensitive information became available for the public and cybercriminals to use and abuse for financial gain. The current development and spread of telemedicine in the world is unlikely to decrease this trend, although, we hope that after recent cases such as the Vastaamo hack, medical organizations will approach data collection and security with greater responsibility.

The growth in the number of photos of people with documents in their hand and various schemes exploiting them also reflects a trend in the cybergoods game and indicates that any data shared, even with organizations, can potentially end up in the hands of cybercrooks and abused for the purposes of financial gain. The repercussions of such data abuse are very real for the victims as they will have to deal with the loans taken out in their name or services used on the basis of their identity.

At the same time, there is some good news when it comes to the safety of personal accounts and gaining access to specific emails and social media accounts. With improved security measures employed at the industry level, targeting and hijacking a specific individual’s account is very costly, and in most cases, not doable. In this sphere there is evidence of an interesting dynamic of cybercriminals scamming each other, with most cybercrooks unable to deliver what they advertise. That does not, however, eliminate the threat entirely: provided they have the funds and their order is big enough, the criminals may still be able to buy what they want.

The overview of the types of data available on dark markets suggests that at least some of the offers might be of interest to especially determined doxers. While we believe that such cases are unlikely due to their cost right now, things might change depending largely on the determination of the abusers to dox an individual.

Protecting your data and yourself

With our ever-growing online presence and footprint, it is almost impossible to be completely anonymous online. A determined person with some computer skills, especially if they have access to privileged information (say, a private investigator or a law enforcement officer), will find at least some data about you given enough time.

EXAMPLE: Kevin Mitnick shares a story in his book “The Art of Invisibility” about how he managed to find out the SSN, city of birth and the mother’s maiden name of a reporter who thought she had a very minimal online presence (he did it with her consent). To do so, he used his access to a specialized web resource for private investigators. People who usually enjoy privacy can also be tracked to their homes if you have specific data: a geolocation dataset from a marketing company obtained by the New York Times in 2019 showed the GPS location over time of senior US government officials, policemen and even acquaintances of Johnny Depp and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

This means that online privacy is almost always about assessing the risks that you face and taking appropriate measures to mitigate them. If you think you might anger a few low-caliber online trolls with a tweet, it is enough to hide your email address from your social network profile. If you are a political reporter covering extremist movements, you need more control of your digital footprint. Below, we describe a few basic steps that will be sufficient against doxing for an average internet user.

Know what they know

The first thing to do if you want to protect yourself against doxing is to research what the Internet knows about you. Try googling your name, combine it with some other data about you such as your place of residence or year of birth to narrow down the results. Try searching for your online handles and emails as well. If your name is not very popular, you can even subscribe to notificationы from Google in case it pops up somewhere on the web.

Apart from Google, there are so-called people search engines such as BeenVerified that allow background checks to be conducted on people using open web data or government records. Publishing this kind of information online might be illegal depending on the country, so availability of such websites differs in various jurisdictions.

If you have public social media profiles, review the posts. Check if they contain geotags with places that you frequent, such as your home or office, or photos that can reveal their location. Of course, not all photos are dangerous, but the more specific they are, the more risk they carry. Scout your older posts for some more private data, such as names of your family members. If you have a private profile, check if you actually know all the people in your friend list.

Remember that, besides social networks per se, there are many other applications that have a social component and can reveal information about you, ranging from languages that you learn to your level of sexual activity. Pay special attention to apps that record some sort of geodata, such as fitness tracking applications. Check that your account in such apps is private.

EXAMPLE: In 2018, a security researcher noted that there were spots with a high level of activity in a dataset of user activity in Strava, a fitness app, in the Middle East. These spots, cross-referenced with Google Maps, gave away the location of US military bases in the region.

Finally, check if your data was leaked in data breaches. Leak monitoring is usually built into password managers and web browsers, but you can also use a dedicated service like HaveIBeenPwned. If your email is found in a leak, you can assume that any other information from the breached info is available somewhere (e.g. your home address if the breached service is a web store, or your favorite running routes if it is a fitness tracker).

Remove what you can

If you think that the information about you on the internet can be used against you, try to get rid of it. In the case of social networks, it is usually relatively easy: you either remove the posts with private data or make your profile private.

With other websites, check if you can just remove or disable your account. Otherwise, check if the website has a complaint or information removal form and use it. If not, try to contact the administrators directly. If your jurisdiction has strict data privacy laws, such as GDPR or CCPA, it is easier for a service to just remove your data than face a regulator and the threat of huge fines.

If some information is impossible to remove from the source, you can ask the search engine to remove links to websites containing your private data from search results by exercising the so-called right to be forgotten. Whether you can do so depends on the search engine and jurisdiction.

EXAMPLE: One of our researchers uses a smart watch with an application that traces his physical activity and helps him monitor his progress when jogging. One day he was approached by another runner that he didn’t know. Turns out the guy knew his name and where he runs – all thanks to this application, which did not only tracked his data but also shared it in its internal social network. While this strange occurrence didn’t result in any harm and the intention of the application was to help fellow runners meet each other, it is clear how knowledge of someone’s location and regular jogging route could be used against them – possibly by less friendly strangers.

Protect yourself

Doxing is most devastating when the data being published is private, i.e., cannot be found on the internet. An adversary can obtain this data by hacking into the accounts and services that you use. To minimize the risks of being hacked, follow these simple rules:

- Never reuse your passwords across accounts. Use a unique password for each account and a password manager to store them.

- Protect your devices with fingerprint/face scan or with a PIN or password.

- Use two-factor authentication. Remember that using an application that generates one-time codes is more secure than receiving the second factor via SMS. If you need additional security, invest in a hardware 2FA key.

- Beware of phishing email and websites.

If you are ready to invest a bit more effort into protecting your privacy, here are some additional ways to protect your personal information or check if your passwords or data have become compromised without your knowledge:

- Think twice before you post on social media channels. Could there be unforseen consequences of making your views or information public? Could content be used against you or to your detriment now or in the future?

- To make sure people close to home, including family, friends or colleagues, can’t access your devices or accounts without your consent, never share passwords even if it seems like a good idea or convenient to do so. Writing them on a sticky note next to your screen might be helpful for you, but it may also help others to access things you don’t want them to.

- Ensure you always check permission settings on the apps you use, to minimize the likelihood of your data being shared or stored by third parties – and beyond – without your knowledge. You might end up giving consent by default, so it is always worth double-checking before you start using an app or service.

- There is no substitute for strong and robust passwords. Use a reliable security solution like Kaspersky Password Manager to generate and secure unique passwords for every account, and resist the temptation to re-use the same one over and over again.

- Password managers also allow personal data to be stored in an encrypted private vault where you can upload your driver’s licenses, passports/IDs, bank cards, insurance files and other valuable documents and manage them securely.

- To find out if any of the passwords you use to access your online accounts have been compromised, use a tool such as Kaspersky Security Cloud. Its Account Check feature allows users to inspect their accounts for potential data leaks. If a leak is detected, Kaspersky Security Cloud provides information about the categories of data that may be publicly accessible so that the individual affected can take appropriate action.

When it is too late

If you have fallen victim to doxing, you can try to contact the moderators of the website where your data was leaked or flag the posts with your data on the social network to have it removed before the information spreads.

Note that usually the goal of doxers is to cause the victim stress and psychological discomfort. Do not engage with trolls, make your accounts private and seek comfort with your friends, relatives and offline activities. It takes a short time for an online mob to give up on their victim and move on if you do not give them additional reasons to attack you.

However, if you receive threats or fear for your physical safety, you might want to contact law enforcement. In this case, remember to document what is going on, for example screenshot the threats, to provide law enforcement officers with additional evidence.

To sum up: take good care of yourself and your data

The digital world provides us with endless opportunities to express our individuality and share our stories, but we need to make sure it is a safe place to express ourselves. As this research shows, our data is valuable not only to us but to many other users with malicious intentions – ranging from an expression of dissatisfaction with your actions to cybercriminals who thrive on profiting off personal data. That’s why it’s crucial to know how to protect it.

An important point to remember here is that cybercriminals are not the only ones who can use our data to cause harm – with new phenomena such as doxing, users need to be aware that they can never know how someone can capitalize on their data. Approaching personal data sharing with responsibility is a must-have skill nowadays that will help keep us safer in the storms of the digital world.

If you like the site, please consider joining the telegram channel or supporting us on Patreon using the button below.