How we developed our simple Harbour decompiler

https://github.com/KasperskyLab/hb_dec

Every once in a while we get a request that leaves us scratching our heads. With these types of requests, existing tools are usually not enough and we have to create our own custom tooling to solve the “problem”. One such request dropped onto our desk at the beginning of 2018, when one of our customers – a financial institution – asked us to analyze a sample. This in itself is nothing unusual – we receive requests like that all the time. But what was unusual about this particular request was that the sample was written in ‘Harbour’. For those of you who don’t know what Harbour is (just like us), you can take a look here, or carry on reading.

Harbour is a programming language originally designed by Antonio Linares that saw its first release in 1999. It’s based on the old Clipper system and is primarily used for the creation of database programs.

Understanding Harbour’s internals

Let us take a “Hello, world” example from the Harbour repository tests – hello.prg.

// Typical welcome message PROCEDURE Main() ? "Hello, world!" RETURN

Figure 1: Harbour version of “Hello, world!”

It prints the “Hello, world!” message to the terminal. For that, you need to build a Harbour binary to execute the code (there are also other ways to run it without building a binary, but we chose this path because the received sample was an executable).

Compiling is as simple as calling:

hbmk2.exe hello.prg

This command will generate C code and compile the C code into the final executable. The generated C code for hello.prg can be found in Figure 2.

/*

* Harbour 3.0.0 (Rev. 16951)

* MinGW GNU C 4.5.2 (32-bit)

* Generated C source from "hello.prg"

*/

#include "hbvmpub.h"

#include "hbinit.h"

HB_FUNC( MAIN );

HB_FUNC_EXTERN( QOUT );

HB_INIT_SYMBOLS_BEGIN( hb_vm_SymbolInit_HELLO )

{ "MAIN", {HB_FS_PUBLIC | HB_FS_FIRST | HB_FS_LOCAL}, {HB_FUNCNAME( MAIN )}, NULL },

{ "QOUT", {HB_FS_PUBLIC}, {HB_FUNCNAME( QOUT )}, NULL }

HB_INIT_SYMBOLS_EX_END( hb_vm_SymbolInit_HELLO, "hello.prg", 0x0, 0x0003 )

#if defined( HB_PRAGMA_STARTUP )

#pragma startup hb_vm_SymbolInit_HELLO

#elif defined( HB_DATASEG_STARTUP )

#define HB_DATASEG_BODY HB_DATASEG_FUNC( hb_vm_SymbolInit_HELLO )

#include "hbiniseg.h"

#endif

HB_FUNC( MAIN )

{

static const HB_BYTE pcode[] =

{

36,5,0,176,1,0,106,14,72,101,108,108,111,44,

32,119,111,114,108,100,33,0,20,1,36,7,0,7

};

hb_vmExecute( pcode, symbols );

}

Figure 2: Generated C code for hello.prg

You can see that the MAIN function starts the Harbour virtual machine (HVM) function hb_vmExecute with two parameters: the pcode, precompiled Harbour code; and the symbols, which are defined by a different macro above the MAIN function. As you can imagine, the pcode (portable code) contains the instructions that are interpreted by the HVM. You can find the official explanation of the pcode in the link below.

https://github.com/harbour/core/blob/master/doc/pcode.txt

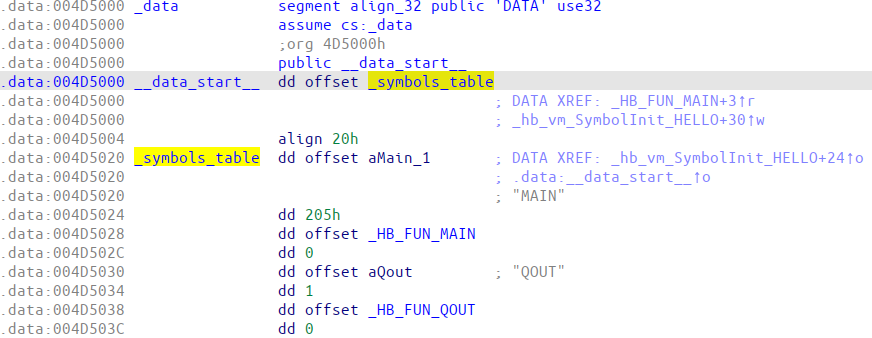

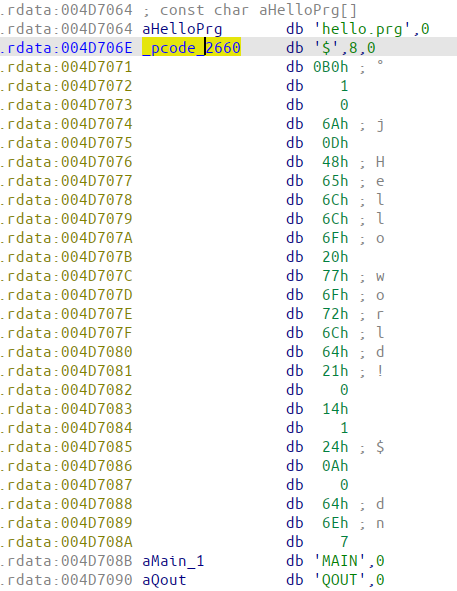

After the C program has been compiled (by MINGW in our case), we find almost the same structures inside it: symbol table and pcode (Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively).

Figure 3: Harbour symbols table of hello.exe

Figure 4: Harbour pcode of hello.exe

Decompilation

Back to our sample. We now know that we need to find the pcodes and symbols in the executable and see which opcodes belong to which instruction. If we do this, we can get a fair grasp of how the program works. As you can probably guess, there were no readily available tools to do this. So, we wrote our own.

The aim of our decompiler is to make the bytecode readable by a human. We chose to mix the resulting pseudocode in assembler with C (it’s still hard to read in some places, but was fine for our purposes).

./hb_dec hello.exe

e_magic : 5a4d

e_lfanew(PE) : 80

OptionalHeader.AddressOfEntryPoint: 1160

OptionalHeader.ImageBase: 400000

Found hb source filename: hello.prg

Cheсking if this program compiled by MINGW

.data section found

usual padding size correct (20==20)

yes, it is MINGW

hb_symbols_table_va : 4d5020

hb_symbols_table_raw_offset : d4620

hb_symb #0

name: MAIN

scope.value: 205 [ HB_FS_PUBLIC | HB_FS_FIRST | HB_FS_LOCAL ]

value.pFunPtr: 4013c0

pDynSym: 0

===

pcode offset 4d706e for local function MAIN

===

hb_symb #1

name: QOUT

scope.value: 1 [ HB_FS_PUBLIC ]

value.pFunPtr: 44b7c0

pDynSym: 0

===

hb_symb #2

name: EVAL

scope.value: 1 [ HB_FS_PUBLIC ]

value.pFunPtr: 442860

pDynSym: 0

===

hb_symb #3

name: hb_stackInit

scope.value: 2 [ HB_FS_STATIC ]

value.pFunPtr: 0

pDynSym: 0

===

found pcode for local function MAIN 4D708A - 4D706E = 1C

PCODE for local function MAIN pcode size 1C

00000000 24 05 00 /* currently compiled source code line number 5 */

00000003 B0 01 00 push offset QOUT

00000006 6A 0E 48 65 6C 6C 6F 2C ... push offset "Hello, world!"

00000016 14 01 call 1 /* call a function from STACK[-1] and discard the results */

00000018 24 07 00 /* currently compiled source code line number 7 */

0000001b 07 end proc

Figure 5 – The decompiled output of the hello.prg program

Figure 5 also shows that Harbour is a stack-based compiler. The first push argument is the function name, after which the variables are pushed, followed by the call 1 command, where 1 is the number of function parameters to be popped. The above lines can thus be interpreted in C pseudocode as:

QOUT("Hello, world!");

We hope this decompiler makes analyzing samples written in Harbour a little bit easier for others as well.