More than a Dozen Obfuscated APT33 Botnets Used for Extreme Narrow Targeting

This blog was originally published on November 13, 2019.

By Feike Hacquebord, Cedric Pernet, and Kenney Lu

The threat group regularly referred to as APT33 is known to target the oil and aviation industries aggressively. This threat group has been reported on consistently for years, but our recent findings show that the group has been using about a dozen live Command and Control (C&C) servers for extremely narrow targeting. The group puts up multiple layers of obfuscation to run these C&C servers in extremely targeted malware campaigns against organizations in the Middle East, the U.S., and Asia.

| This article is part of a research paper that dives into cyberattacks on the oil and gas industry. It provides a more comprehensive look at APT33 and other critical threats. Read the full paper here. |

We believe these botnets, each comprising a small group of up to a dozen infected computers, are used to gain persistence within the networks of select targets. The malware is rather basic, and has limited capabilities that include downloading and running additional malware. Among active infections in 2019 are two separate locations of a private American company that offers services related to national security, victims connecting from a university and a college in the U.S., a victim most likely related to the U.S. military, and several victims in the Middle East and Asia.

APT33 has also been executing more aggressive attacks over the past few years. For example, for at least two years the group used the private website of a high-ranking European politician (a member of her country’s defense committee) to send spear phishing emails to companies that are part of the supply chain of oil products. Targets included a water facility that is used by the U.S. army for the potable water supply of one of its military bases.

These attacks have likely resulted in concrete infections in the oil industry. For example, in the fall of 2018, we observed communications between a U.K.-based oil company with computer servers in the U.K. and India and an APT33 C&C server. Another European oil company suffered from an APT33 related malware infection on one of their servers in India for at least 3 weeks in November and December 2018. There were several other companies in oil supply chains that had been compromised in the fall of 2018 as well. These compromises indicate a big risk to companies in the oil industry, as APT33 is known to use destructive malware.

| Date | From Address | Subject |

| 12/31/16 | [email protected] | Job Opportunity |

| 4/17/17 | [email protected] | Vacancy Announcement |

| 7/17/17 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 9/11/17 | [email protected] | Job Opportunity |

| 11/20/17 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 11/28/17 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 3/5/18 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 7/2/18 | [email protected] | Job Opportunity SIPCHEM |

| 7/30/18 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 8/14/18 | [email protected] | Job Openning |

| 8/26/18 | [email protected] | Latest Vacancy |

| 8/28/18 | [email protected] | Latest Vacancy |

| 9/25/18 | [email protected] | AramCo Jobs |

| 10/22/18 | [email protected] | Job Openning at SAMREF |

Table 1. Spear phishing campaigns of APT33. Source: Trend Micro’s Smart Protection Network

The first two email addresses in the table above (ending in .com and .aero) are being spoofed by the threat group. However, the addresses ending in .ga are from the attacker’s own infrastructure. The addresses are all impersonating known aviation and oil and gas companies.

Aside from the relatively noisy attacks of APT33 against oil product supply chains, we found that APT33 has been using several C&C domains for small botnets comprised of about a dozen bots each.

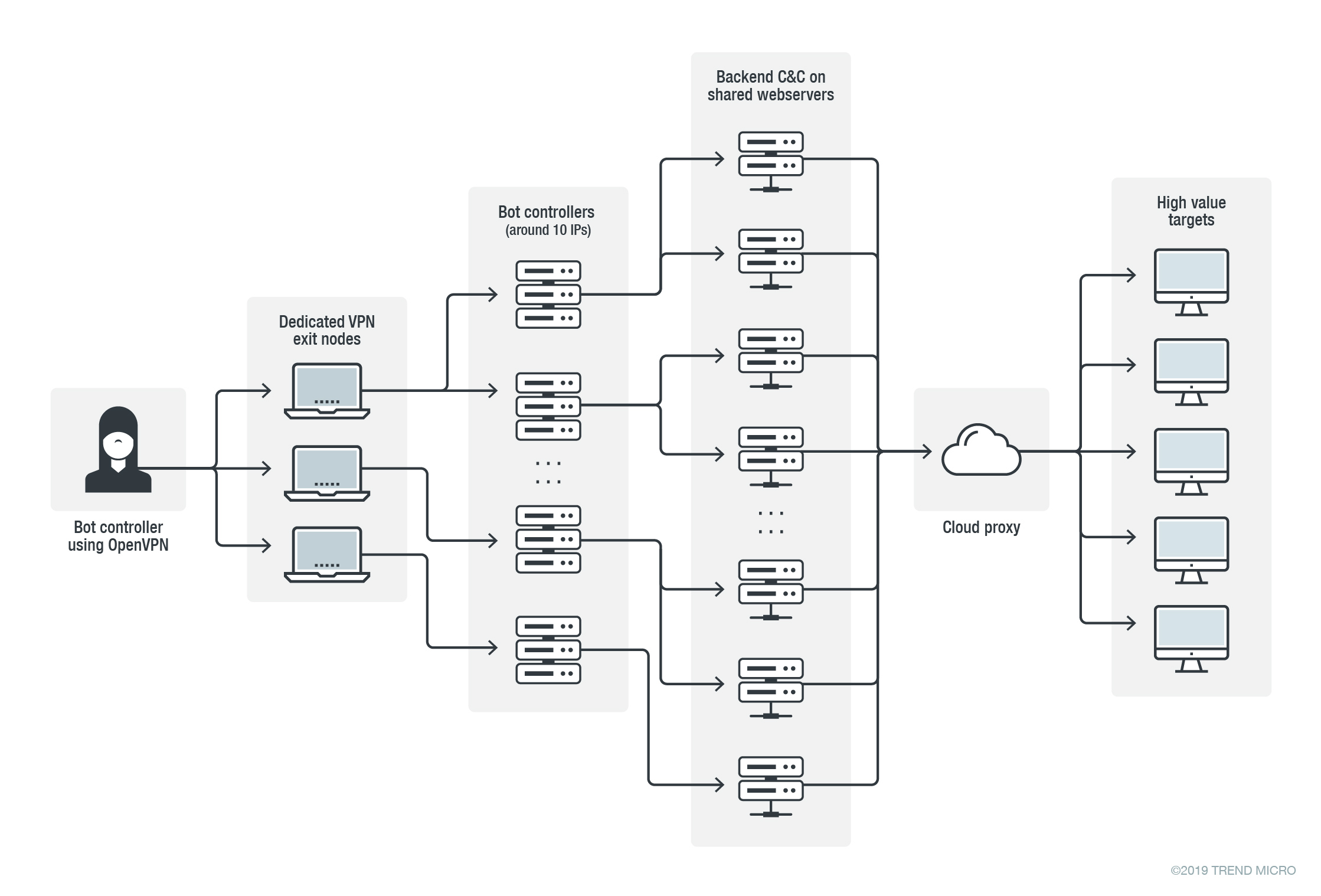

It appears that APT33 took special care to make tracking more difficult. The C&C domains are usually hosted on cloud hosted proxies. These proxies relay URL requests from the infected bots to backends at shared webservers that may host thousands of legitimate domains. The backends report bot data back to a data aggregator and bot control server that is on a dedicated IP address. The APT33 actors connect to these aggregators via a private VPN network with exit nodes that are changed frequently. The APT33 actors then issue commands to the bots and collect data from the bots using these VPN connections.

In fall of 2019 we counted 10 live bot data aggregating and bot controlling servers and tracked a couple of them for months. These aggregators get data from very few C&C servers (only 1 or 2), with only up to a dozen victims per unique C&C domain. The table below lists some of the older C&C domains that are still live today.

| Domain | Created |

| oorgans.com | 5/28/16 |

| suncocity.com | 5/31/16 |

| zandelshop.com | 6/1/16 |

| simsoshop.com | 6/2/16 |

| zeverco.com | 6/5/16 |

| qualitweb.com | 6/6/16 |

| service-explorer.com | 3/3/17 |

| service-norton.com | 3/6/17 |

| service-eset.com | 3/6/17 |

| service-essential.com | 3/7/17 |

| update-symantec.com | 3/12/17 |

Table 2. APT33 C&C domains for extreme narrow targeting

Figure 1. Schema showing the multiple obfuscation layers that APT33 uses

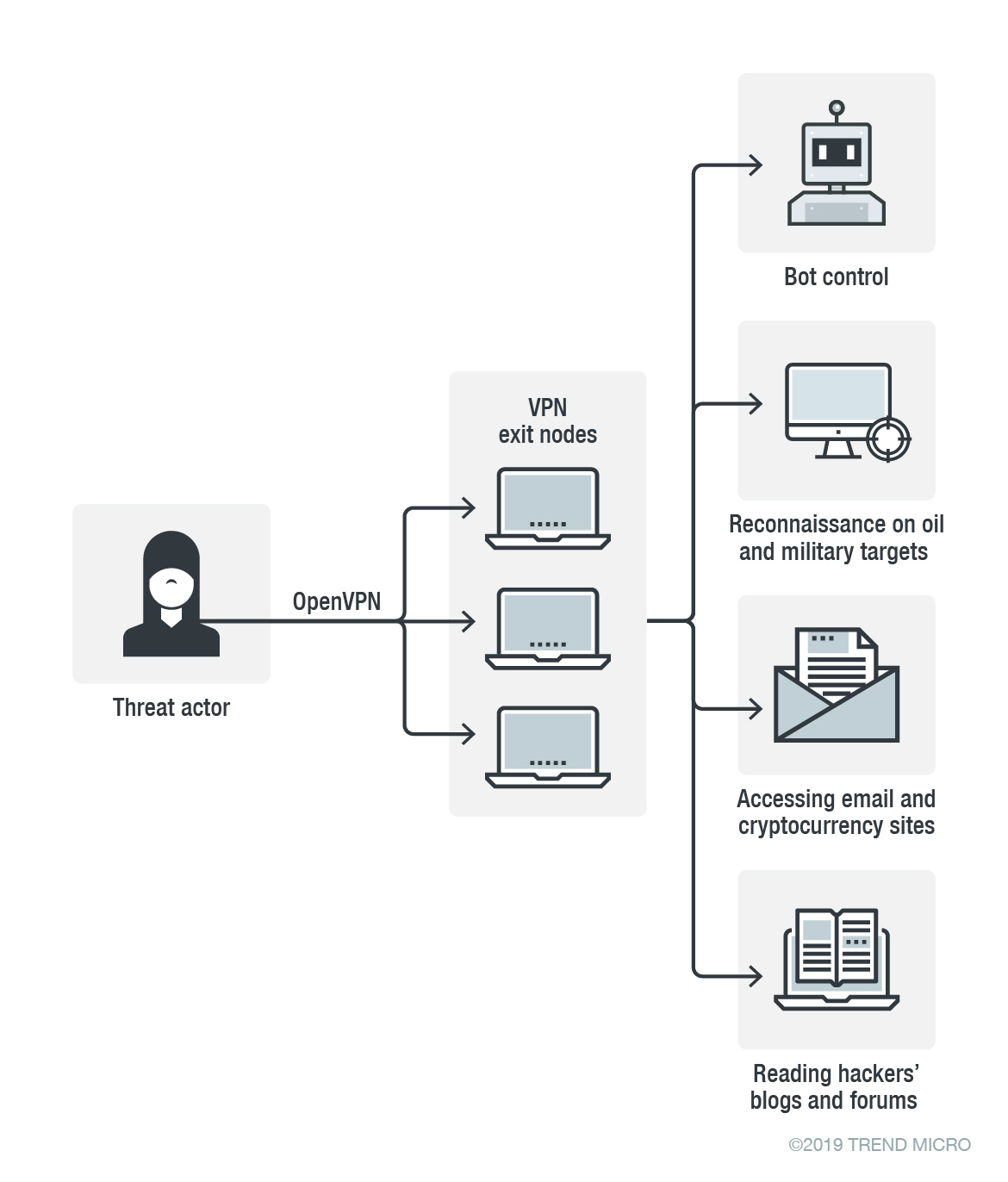

Threat actors often use commercial VPN services to hide their whereabouts when administering C&C servers and doing reconnaissance. But besides using VPN services that are available for any user, we also regularly see actors using private VPN networks that they set up for themselves.

Setting up a private VPN can be easily done by renting a couple of servers from datacenters around the world and using open source software like OpenVPN. Though the connections from private VPN networks still come from seemingly unrelated IP addresses around the world, this kind of traffic is actually easier to track. Once we know that an exit node is mainly being used by a particular actor, we can have a high degree of confidence about the attribution of the connections that are made from the IP addresses of the exit node. For example, besides administering C&C servers from a private VPN exit node, an actor might also be doing reconnaissance of targets’ networks.

APT33 likely uses its VPN exit nodes exclusively. We have been tracking some of the group’s private VPN exit nodes for more than a year and we have listed known associated IP addresses in the table below. The indicated timeframes are conservative; it is likely that the IP addresses have been used for a longer time.

| IP address | First seen | Last seen |

| 5.135.120.57 | 12/4/18 | 1/24/19 |

| 5.135.199.25 | 3/3/19 | 3/3/19 |

| 31.7.62.48 | 9/26/18 | 9/29/18 |

| 51.77.11.46 | 7/1/19 | 7/2/19 |

| 54.36.73.108 | 7/22/19 | 10/05/19 |

| 54.37.48.172 | 10/22/19 | 11/05/19 |

| 54.38.124.150 | 10/28/18 | 11/17/18 |

| 88.150.221.107 | 9/26/19 | 11/07/19 |

| 91.134.203.59 | 9/26/18 | 12/4/18 |

| 109.169.89.103 | 12/2/18 | 12/14/18 |

| 109.200.24.114 | 11/19/18 | 12/25/18 |

| 137.74.80.220 | 9/29/18 | 10/23/18 |

| 137.74.157.84 | 12/18/18 | 10/21/19 |

| 185.122.56.232 | 9/29/18 | 11/4/18 |

| 185.125.204.57 | 10/25/18 | 1/14/19 |

| 185.175.138.173 | 1/19/19 | 1/22/19 |

| 188.165.119.138 | 10/8/18 | 11/19/18 |

| 193.70.71.112 | 3/7/19 | 3/17/19 |

| 195.154.41.72 | 1/13/19 | 1/20/19 |

| 213.32.113.159 | 6/30/19 | 9/16/19 |

| 216.244.93.137 | 12/10/18 | 12/21/18 |

Table 3. IP addresses associated with a few private VPN exit nodes connected to APT33

It appears that these private VPN exit nodes are also used for reconnaissance of networks that are relevant to the supply chain of the oil industry. More concretely, we have witnessed some of the IP addresses in Table 3 doing reconnaissance on the network of an oil exploration company and military hospitals in the Middle East, as well as an oil company in the U.S..

Figure 2. APT33’s usage of a private VPN network

APT33 used its private VPN network to access websites of penetration testing companies, webmail, websites on vulnerabilities, and websites related to cryptocurrencies, as well as to read hacker blogs and forums. APT33 also has a clear interest in websites that specialize in the recruitment of employees in the oil and gas industry. We recommend companies in the oil and gas industry to cross-relate their security log files with the IP addresses listed above.

Security recommendations

The continued modernization of facilities for oil, gas, water, and power is making it more difficult to secure them. Outright attacks, readily exploitable vulnerabilities, as well as exposed SCADA/HMI are serious issues. Here are some of the best practices that these organizations can adopt:

- Establish a regular patching and update policy for all systems. Download patches as soon as possible to prevent cybercriminals from exploiting these security flaws.

- Improve employee awareness on the latest attack techniques that cybercriminals use.

- IT administrators should apply the principle of least privilege to make monitoring of inbound and outbound traffic easier.

- Install a multilayered protection system that can detect and block malicious intrusions from the gateway to the endpoint.

Securing supply chains to these complex and often multinational systems is also difficult, as they usually have necessary third-party suppliers that are embedded in their core operations. These parties may be overlooked in terms of security, and vulnerabilities in the communication or connections with them are often targeted by cybercriminals. Read our supply chain attack research and our security recommendations here.

As mentioned above, APT33 is known to use spear phishing emails to gain entry into a target’s network, and given their malicious activity the threat is definitively serious. To defend against spam and email threats, businesses can consider Trend Micro endpoint solutions such as Trend Micro Smart Protection Suites and Worry-Free

endpoint solutions such as Trend Micro Smart Protection Suites and Worry-Free Business Security. Trend Micro Deep Discovery

Business Security. Trend Micro Deep Discovery has an email inspection layer that can protect enterprises by detecting malicious attachments and URLs. Trend Micro

has an email inspection layer that can protect enterprises by detecting malicious attachments and URLs. Trend Micro Hosted Email Security is a no-maintenance cloud solution that delivers continuously updated protection to stop spam, malware, spear phishing, ransomware, and advanced targeted attacks before they reach the network. It protects Microsoft Exchange, Microsoft Office 365, Google Apps, and other hosted and on-premises email solutions.

Hosted Email Security is a no-maintenance cloud solution that delivers continuously updated protection to stop spam, malware, spear phishing, ransomware, and advanced targeted attacks before they reach the network. It protects Microsoft Exchange, Microsoft Office 365, Google Apps, and other hosted and on-premises email solutions.

Indicators of Compromise

| File name | SHA256 | Detection Name |

| MsdUpdate.exe | e954ff741baebb173ba45fbcfdea7499d00d8cfa2933b69f6cc0970b294f9ffd | Trojan.Win32.NYMERIA.MLR |

| MsdUpdate.exe | b58a2ef01af65d32ca4ba555bd72931dc68728e6d96d8808afca029b4c75d31e | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AB |

| MsdUpdate.exe | a67461a0c14fc1528ad83b9bd874f53b7616cfed99656442fb4d9cdd7d09e449 | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AC |

| MsdUpdate.exe | c303454efb21c0bf0df6fb6c2a14e401efeb57c1c574f63cdae74ef74a3b01f2 | Trojan.Win32.NYMERIA.MLW |

| MsdUpdate.exe | 75e6bafc4fa496b418df0208f12e688b16e7afdb94a7b30e3eca532717beb9ba | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AD |

| MsdUpdate.exe | 8fb6cbf6f6b6a897bf0ee1217dbf738bce7a3000507b89ea30049fd670018b46 | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AD |

| DysonPart.exe | ba9d76cca6b5c7308961cfe3739dc1328f3dad9a824417fad73b842b043daa1a | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AD |

| Unknown | 07e1baf1d0207a139bcf39c60354666496e4331381d36eef9359120b1d8497f1 | Trojan.Win32.SCAR.AD |

Updated on November 27, 2019 at 11:00 PM PST to add new information about a C&C domain.

The post More than a Dozen Obfuscated APT33 Botnets Used for Extreme Narrow Targeting appeared first on .